Differentiated Thyroid Cancer

What is differentiated thyroid cancer?

Differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) includes papillary thyroid cancer and follicular thyroid cancer. Papillary thyroid cancer is the most common form of thyroid cancer in both children and adults and represents about 85 to 90 percent of all DTC diagnoses. Follicular thyroid cancer accounts for only 5 to 10 percent of pediatric patients with differentiated thyroid cancer.

Papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) in children and adolescents does not behave the same as it does in adult patients. Even when PTC has spread to the lymph nodes or lungs, pediatric patients with the disorder have much better outcomes compared to adults. About 40 to 60 percent of children diagnosed with differentiated thyroid cancer will have papillary thyroid cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes; for about 15 percent, the PTC has spread to their lungs.

Unlike papillary thyroid cancer, follicular thyroid cancer (FTC) is usually found as a solitary thyroid nodule. While follicular thyroid cancer has less chance of spreading to the lymph nodes in the neck, there is a higher chance of the cancer spreading to distant sites in the body, such as the bones, because FTC can invade blood vessels.

No matter how much the cancer has spread, pediatric patients with differentiated thyroid cancer have more than a 95 percent survival rate 20 to 30 years after treatment. When properly evaluated and treated, the vast majority of pediatric patients with differentiated thyroid cancer will go on to lead productive and rewarding lives.

The primary challenge when treating pediatric patients with differentiated thyroid cancer is reducing the complications that can result from medical and surgical treatment for the disorder.

Signs and symptoms of DTC

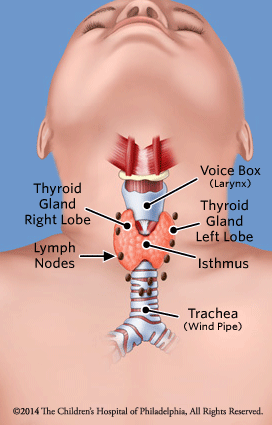

Most patients with differentiated thyroid cancer do not have any obvious signs or symptoms. In most cases, a thyroid nodule is discovered during a physical exam or through a radiology study for a non-thyroid-related head or neck issue.

When symptoms are present, they may include:

- Feeling a lump in the neck when at rest, lying down, or while eating or drinking

- Change in voice

Causes of differentiated thyroid cancer

Several genes have been associated with the development of differentiated thyroid cancer. Unfortunately, at this time, knowing the specific gene mutation does not allow us to predict the behavior, response to therapy, or prognosis of thyroid cancer in children and adolescents.

One of the most active research areas of the Pediatric Thyroid Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) is to identify specific molecular markers, growth factors and proteins that would give us this type of information and capability. Learn about our thyroid disease research.

Risk factors for differentiated thyroid cancer

There are a number of factors that can increase your child’s risk of developing differentiated thyroid cancer including: ionizing radiation, age and gender, autoimmune disease, as well as a family history of thyroid cancer.

Ionizing radiation

Previous exposure to ionizing radiation has been identified as a risk factor for developing thyroid cancer. Fortunately, only a very small percentage of pediatric patients have a history of this risk factor. Outside of rare environmental exposure — such as the Chernobyl and Fukushima nuclear reactor accidents in 1986 and 2011, respectively — exposure to ionizing radiation is most often associated with treatment of another cancer.

Examples of previous medical treatments include:

- Head and neck radiation for brain or facial tumors

- Treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma

- Total body irradiation in preparation for bone marrow transplant

The risk of developing thyroid nodules and thyroid cancer is higher for girls, those exposed to lower doses of radiation, and those exposed to radiation at a young age.

Thyroid lesions rarely develop within the first 3-5 years after exposure. In fact, thyroid lesions may develop as late as three to four decades after exposure. Because of this, at CHOP we recommend regular thyroid physical exams to cancer survivors who received head-and-neck or total-body exposure to radiation. These exams should start within a year of the original cancer diagnosis, and thyroid ultrasounds should start within 3-5 years of diagnosis.

In addition to thyroid nodules and thyroid cancer, patients exposed to ionizing radiation are at risk of developing hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism. Thyroid function tests should be a regular part of screening for these patients.

Age and gender

Adolescent girls between the ages of 15 and 18 have the highest rate of developing papillary thyroid cancer. While there are many potential reasons, none fully explains the observed risk for this subgroup of patients.

Autoimmune thyroid disease

Patients with autoimmune thyroid disease, most frequently Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (also known as chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis), are also at increased risk of developing thyroid nodules and thyroid cancer. This is an area with significant controversy, complicated by the fact that in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease, the appearance of abnormal thyroid tissue and enlarged lymph nodes on ultrasound may be unrelated to thyroid cancer. Therefore, if a thyroid ultrasound is performed, the results must be interpreted with these known associations in mind, and by radiologists with experience reading pediatric thyroid ultrasounds.

Family history of thyroid cancer

Once a family member is diagnosed with either papillary or follicular thyroid cancer, there appears to be a small — but significant — risk of other family members developing the same type of cancer. The risk may be isolated to the development of thyroid cancer or may be associated with an increased risk of developing other forms of cancer or thyroid-related medical conditions such as PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome, DICER1 syndrome, and familiar adenomatous polyposis.

Your child’s doctor will discuss the risks in more detail with you and your family and answer any questions you might have.

Testing and diagnosis of differentiated thyroid cancer

If there is any indication your child may have thyroid cancer, they should be referred to dedicated program, like the Pediatric Thyroid Center at CHOP, that has the experience, expertise and resources to fully evaluate your child.

At Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, a diagnosis of differentiated thyroid cancer begins with a complete medical history and comprehensive physical examination that includes evaluation of the thyroid and the lymph nodes in the neck. Watch CHOP Endocrinologist Andrew J. Bauer, MD, perform a pediatric thyroid exam.

Clinical experts may use a variety of diagnostic tests including:

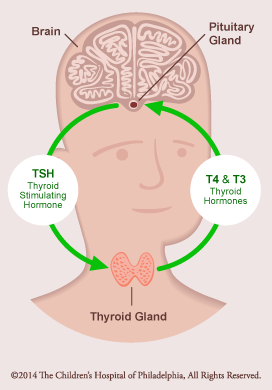

- Blood test to measure the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level to determine how well your child’s thyroid is working.

- Thyroid ultrasound (or thyroid scan) to learn about the size, number, appearance and location of any thyroid nodules and abnormal lymph nodes.

- Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) to collect cells from the thyroid, and possibly lymph nodes, to be examined under a microscope.

- A nuclear medicine uptake and scan will be ordered if your child’s TSH level is low or suppressed. This test determines how well the thyroid tissues are absorbing iodine.

Treatment for differentiated thyroid cancer

At CHOP, experts at the Pediatric Thyroid Center take a team approach to treatment for children with differentiated thyroid cancer. Our board-certified team of endocrinologists, oncologists, pediatric surgeons, pathologists, radiologists and nurses collaborate to provide your child with individualized care and the best possible outcome.

Our Center is led by Andrew J. Bauer, MD, a world-renowned endocrinologist and researcher, who is often sought for second opinions on difficult-to-diagnose thyroid disorders. Dr. Bauer is a member of the American Thyroid Association (ATA) and co-chaired an international ATA task force that created the first guidelines for evaluating and managing thyroid nodules and thyroid cancer in children.

Thyroid cancer is treated with surgery and radioactive iodine. At Children’s Hospital, our clinicians have the expertise to determine whether your child needs more or less extensive surgery, and a single or repeated doses of radioactive iodine. These decisions can reduce complication rates and optimize immediate and long-term quality of life for your child.

Clinicians from the Pediatric Thyroid Center will discuss the treatment plan with your child and family, and explain what to expect before, during and after surgery. The team will also detail when your child should begin a low-iodine diet, stop thyroid hormone therapy, and when radioactive iodine (RAI) whole body scans and treatment may begin.

Thyroid surgery

The type and extent of thyroid surgery recommended for your child will be based on the results of the fine-needle aspiration and preoperative evaluation. Preoperative staging should include a complete thyroid and neck ultrasound, and may include a neck MRI or chest CT scan. PET scans are rarely needed as these findings usually do not affect the surgical approach.

For patients who have a fine-needle aspiration result that is “indeterminate,” the most common surgery is to remove half of the thyroid gland, a procedure known as a lobectomy. Surgically removing the thyroid nodule allows the pathologist to more completely evaluate the tissue to determine the appearance and behavior of the cells.

If there are indeterminate nodules in both sides of the thyroid gland — or if the patient has an increased risk of thyroid cancer based on personal or family history — complete removal of the thyroid gland is recommended. This procedure is called a total thyroidectomy.

Risks of thyroid surgery

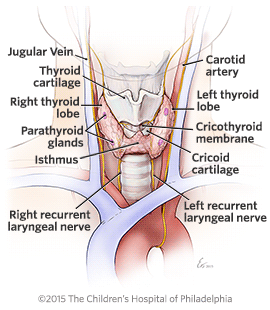

The two most common risks of thyroid surgery include damage to the parathyroid glands or the recurrent laryngeal nerves, structures that are directly attached to the thyroid gland.

- Parathyroid glands: There are four parathyroid glands, two attached to the back of each thyroid lobe. They are about the size of a pencil eraser or pea. The parathyroid glands control the level of calcium in the body. Damage to the parathyroid glands can affect calcium levels and cause significant health risks if left untreated.

- Recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN): The RLN is very thin, about the diameter of a piece of angel hair pasta. The RLN controls the vocal cords and helps protect the airway so food, liquid or other items do not enter the lungs.

The risks of thyroid surgery can be decreased by having the operation performed by an experienced surgical team that completed at least 30 thyroid surgeries per year. The surgeons at the Pediatric Thyroid Center at CHOP perform more than 75 thyroid surgeries a year. The permanent complication rate for thyroid surgery patients at CHOP is less than 2 percent — significantly lower than the national average.

What to expect after surgery

Some patients who undergo a lobectomy may be able to go home the same day as surgery. The majority of patients will need to remain in the Hospital for two to three days after a thyroidectomy. This allows your child time to recover, ensure their pain is under control, and monitor for any potential side effects of surgery such as low calcium levels or RLN damage.

In most cases, surgical pain usually goes away within the first few days and most return to school within four to five days, and full activity within two weeks. The surgical scar is usually 3-4 centimeters in length and located in a skin fold to make it less noticeable. Absorbable sutures (stitches) and steri-strips are used so there is no need to have stitches removed.

Post-surgical evaluation and care

Six to 12 weeks after surgery, patients should be re-evaluated by an experienced endocrinologist to assess if there is any lingering evidence of cancer cells, and determine whether the child would benefit from additional therapy, specifically radioactive iodine.

Radioactive iodine therapy

While all patients will receive thyroid hormone replacement therapy, not all should receive — or would benefit from — radioactive iodine therapy (RAI). RAI destroys any remaining thyroid cells after surgery.

For patients with a low likelihood of developing persistent thyroid cancer, the risks of RAI may outweigh the benefits. Short-term risks of RAI include inflammation of the salivary glands, dry mouth and increased cavities. Long-term risks can include secondary malignancies such as leukemia, salivary gland cancer and others. The greater the dosage and frequency of RAI, the higher the potential risks.

To assess which patients may benefit from radioactive iodine therapy, clinicians at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia refer to the Management Guidelines for Children with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer, released by the American Thyroid Association and co-written by the director of the CHOP’s Pediatric Thyroid Center.

Based on the ATA guidelines, post-surgical patients are examined and their thyroid levels are evaluated to determine if they are at low, intermediate or high risk of cancer recurrence or metastasis (cancer spreading).

RAI is not recommended for patients are low risk. Only patients at intermediate or high risk should be considered for radioactive iodine therapy. These patients should be regularly monitored to determine the best time to start and stop treatment, as well as to assess any side effects of the therapy.

Similarly, radioactive iodine therapy should not be used for patients who received a lobectomy (half of their thyroid removed). If thyroid cancer does spread to the other thyroid lobe, surgery to remove the second lobe would be recommended before RAI is considered.

Learn more about radioactive iodine treatment.

Hormone replacement therapy

After a thyroidectomy, your child will no longer make thyroid hormone on their own. After a lobectomy, your child will likely not make enough thyroid hormone to support their body. Either way, your child will need to take thyroid hormone in order to get their thyroxine hormone (T4) and their thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) in normal ranges.

Thyroid hormone suppression

For patients with thyroid cancer, we prescribe higher doses of thyroid hormone replacement therapy with the goal of making the T4 high-normal or just above the normal limit, with the TSH below the normal limit. This is called suppressive therapy and is used because TSH can stimulate normal — as well as thyroid cancer cells — to grow. Using a suppressive therapy helps to decrease the risk that any remaining cancer cells will grow.

With the higher doses of thyroid hormone replacements, children may experience mild symptoms of hyperthyroidism, including:

- Anxiousness, irritability and/or nervousness

- Poor, restless sleep

- Increased activity (fidgetiness, hyperactivity, restlessness)

- Fatigue

- Increased appetite with or without weight loss

- Increased number of bowel movements per day

- Heat intolerance (always feeling warm)

- Decreased or poor school performance; difficulty concentrating that may be diagnosed as "late-onset" attention deficit disorder

If any of these symptoms are affecting your child’s daily activities, please contact your healthcare team to determine if the dose can be adjusted.

Follow-up care for DTC

Most children treated for differentiated thyroid cancer will need long-term follow-up care into adulthood. In the first few years after surgery, your child will require physical exams and laboratory tests every three to six months.

As time passes — and if there is no evidence of recurrence — follow up exams may become yearly. Your child’s healthcare team will customize a follow-up plan based on your child’s condition and outcome.

After surgery, hormone replacement therapy and radioactive iodine treatment (if used), many children will achieve remission, that is, they will have no clinical evidence, imaging evidence or evidence through laboratory testing of differentiated thyroid cancer. However, others may develop persistent or recurrent thyroid cancer and the cancer may spread to other organs, most commonly the lungs.

Persistent thyroid cancer is defined as evidence of disease by physical exam, laboratory testing and/or imaging six to 12 months after initial treatment. Recurrent thyroid disease is defined as a return of clinical disease after a patient was considered free of disease for six months or more.

Despite extremely favorable outcomes for pediatric patients with differentiated thyroid cancer, recurrence is more common in children than adults. Specific groups that appear to be at highest risk include those who have:

- Cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes in the side of the neck

- Cancer that has spread to the lungs

- Cancer that has spread to the bone

Fortunately, the outcome in children with recurrent disease is much better than in adults.

Recurrent papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) develops in up to 30 percent of children, most commonly in the lymph nodes in the front and side of the neck. In most cases, recurrent PTC can be treated with repeat surgery. Surgical complications are more common with re-exploration of the neck, but can be minimized when performed by an experienced surgeon.

Papillary thyroid cancer may spread to the lungs in up to 15 percent of pediatric patients. The finding of significant metastasis in the neck is a marker of increased risk for spread to the lungs. In contrast to adults, when PTC spreads to the lungs in a child or adolescent, it usually retains the ability to absorb iodine, a status called "iodine avid" disease.

While radioactive iodine (RAI) may be more effective, care will be taken to select a dose and treatment frequency that will avoid adverse effects for your child. More than half of patients will respond to RAI and ultimately achieve remission. However, up to 30 percent of patients with recurrent differentiated thyroid cancer will develop stable, persistent disease. For these patients, repeat RAI is not effective and only increases the risk of side effects.

Patients who develop persistent differentiated thyroid cancer that does not respond to typical treatments will be referred to the Advanced Pediatric Thyroid Cancer Therapeutics Clinic, under the guidance of Theodore W. Leatsch, MD and Dr. Bauer, Director of the Pediatric Thyroid Center at CHOP, endocrinologists will determine which medications are likely to be most effective for your child, when specific medications should start and stop (sometimes in combinations), as well as the correct dosage based on your child’s age, weight and overall condition.

Pulmonary function testing may be performed to assess for lung function, and the decision to treat with repeated doses of RAI must be individualized based on documented response to prior treatment.

Outcomes for differentiated thyroid cancer

The overall disease-specific outcomes for differentiated thyroid cancer among all ages of pediatric patients are excellent. This is true for patients who enter remission after the first treatment as well as patients who require more than one surgery and/or multiple doses of RAI therapy to achieve remission. Prognosis is even excellent for patients who do not achieve remission, but develop stable, persistent disease.

For the subset of patients that achieve remission, there is still an approximate 30 percent risk of recurrence that may occur decades after remission was achieved. Even then, the majority will experience an excellent outcome.

The vast majority of pediatric patients with differentiated thyroid cancer are able to live productive and rewarding lives.