Morgan seemed like a perfectly healthy infant. But at her 4-month checkup, the pediatrician heard a heart murmur.

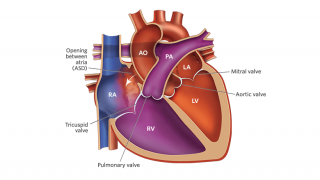

Soon after, a pediatric cardiologist diagnosed an atrial septal defect (ASD), an opening in the tissue separating the heart's upper chambers.

Sometimes referred to as a "hole in the heart," an ASD can be repaired through catheterization or open heart surgery. However, some ASDs will spontaneously close or become smaller in the first few years of life.

Doctors decided that if the ASD didn't close by the time Morgan was 3, they would fix it. Until then, they would monitor her regularly.

While Morgan's growth and development progressed normally, she did have to be hospitalized twice for pneumonia (children with septal defects are more susceptible to infection). Doctors also diagnosed an additional heart problem, pulmonary valve stenosis.

While Morgan's growth and development progressed normally, she did have to be hospitalized twice for pneumonia (children with septal defects are more susceptible to infection). Doctors also diagnosed an additional heart problem, pulmonary valve stenosis.

Morgan also grew into a strong-willed little girl. "A fiery Irish redhead," her mother, Deborah, calls her.

Entrusting CHOP with caring for their precious daughter

When Morgan was 3, the family planned a move from Syracuse, NY, to a Philadelphia suburb. They trusted Morgan's cardiologists, so switching doctors was a source of stress. Then Deborah came across the U.S. News & World Report best hospital listings, which ranked Children's Hospital of Philadelphia as the best pediatric hospital in the nation.

"I came into the room holding the magazine with tears streaming down my face and I told my husband, 'Look where we're going,'" she recalls. "It made our move all the more perfect."

In the fall of 2008, the family came to the Cardiac Center at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia for the first time, for evaluation by Matthew Gillespie, MD. Dr. Gillespie, who also specializes in interventional catheterization, became Morgan's primary cardiologist.

More About ASDs

The Cardiac Center team determined that the ASD hadn't closed, confirming the findings of the doctors in Syracuse. Dr. Gillespie told Deborah and her husband, Ken, that he believed the ASD could be closed through catheterization. However, if the hole were too large, open heart surgery would be necessary.

Cardiac catheterization is often thought of as a diagnostic tool but increasingly can also be used as a less invasive form of treatment for heart defects. During catheterization, while the patient is under general anesthesia, the interventional cardiologist threads a thin tube (a catheter) through a vein in the patient's groin area (or, in newborns, the umbilicus or "belly button") and to the heart. Then, the interventional cardiologist can use a variety of devices, threaded through the catheter, to repair the defect.

Before Morgan’s catheterization, she and her parents waited in the Cardiac Preparation and Recovery Unit. A child life specialist, Kara Lundrum, visited Morgan during the two hours of prep time to help her through the unfamiliar experiences, such as changing into a gown and having an IV placed.

At an earlier appointment, Kara asked Deborah and Ken about their daughter’s favorite things. When they arrived, they found she had prepared a basket of them — dolls, beads, blocks, modeling clay — to keep their daughter distracted.

"Kara was a godsend," Deborah says.

Catheterization to close Morgan’s ASD

When the time came, Morgan's parents walked beside her stretcher to the cath lab, with the anesthesiologist and a nurse. During the procedure, a nurse visited the waiting room with updates. After 90 minutes, Dr. Gillespie arrived with great news: The ASD had been closed.

Morgan stayed overnight in the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit with her mom. After an echocardiogram the next morning, she was discharged. She wore a Holter monitor, which warns of an irregular heartbeat, for 24 hours at home.

"For a few weeks she did revert to very basic things — she wanted to be held, she was afraid of the bandage, she was afraid to bathe," her mother recalls. "All of a sudden, this very bold child was scared."

Follow-up care

An appointment with Dr. Gillespie two months later showed Morgan was recovering perfectly. She will visit once a year for outpatient checkups and the team will monitor her pulmonary valve stenosis, which may resolve on its own.

"A friend's sister just had a baby diagnosed with a heart defect, and I told her, please go to CHOP," Deborah says. "The whole experience has been so positive. Obviously there's concern and worry."

“But everybody was tremendous and the resources that this hospital has to support the kids and the parents are amazing.”

Morgan is back to her favorite pursuits: biking, coloring, reading, playing with her big sister, and wearing her signature pink cowboy boots (which she wore the day Dr. Gillespie fixed her heart). Her fears have diminished, and she speaks of Children's Hospital with fondness.

Her mom says, "The other day we were on our way to the park and she said, 'I think this is the way to Children's Hospital.'"

Originally posted: June 2009