Burnout Is Real; Here’s What You Can Do to Combat It

Published on

Children's DoctorPublished on

Children's DoctorCase: Charlotte, 40, a primary care pediatrician at a busy urban clinic, has been in her current position for 6 years. She is also a parent of a 6- and a 10-year-old. Her spouse is a law firm partner, and Charlotte does the majority of household management with the help of an au pair. She has an interest in quality improvement in healthcare delivery, but she finds she does not have the bandwidth for additional projects. When she initially started at the clinic, she found the pace and complexity energizing. Lately, however, she has found her curiosity has been replaced by dread as she sits down in the evening to attend to her EMR in-basket. While she still gets joy from seeing patients and families, she finds herself being more and more impatient during visits. She works through lunch and rushes to leave the office at day’s end, so often she finishes her work at night. During each vacation, she feels like herself again and returns to work with renewed energy, but it quickly wanes. Charlotte wonders if she should leave her practice or find a nonclinical healthcare job that would allow her to be more relaxed outside work.

Discussion: No one goes into medicine expecting to experience burnout, as Charlotte has, but the reality is that it happens to the majority of physicians at some point during their career. Burnout affects the majority of graduate medical trainees and nearly half of attending physicians in nationwide surveys. First described by Harold Freudenberger in 1974 to describe the exhaustion and depletion he saw in his colleagues at a free clinic for the underserved, burnout is defined as a syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a low sense of personal accomplishment. It differentially affects people in caregiving roles. People affected by burnout may find themselves struggling to muster the energy to face the challenges of the day, having more difficulty empathizing with the suffering of others, or questioning their career choice. Healthcare professionals suffering from burnout are at risk for depression, suicidal ideation, substance use, and broken relationships, and patients of burned out providers are more likely to experience medical errors, poor communication, longer recovery times, and worse satisfaction with their care.

Many factors have contributed to the epidemic of burnout among healthcare professionals, including increased productivity pressure and the burden of clerical and administrative tasks that fall to physicians, which are estimated to occupy twice the number of hours as direct patient interaction each workday.

There is a growing awareness change is needed to prevent ongoing harm from the effects of burnout and to help doctors rediscover joy in the practice of medicine, not only for their benefit, but for the benefit of their patients. All the heavy-hitters—the National Academy of Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medicine Education and the Institute for Health Care Improvement—recognize and are working the problem.

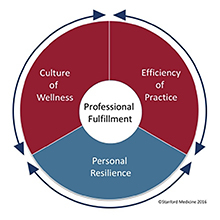

Stanford Professional Fulfillment Model. Used with permission.

The Stanford WellMD center has developed a model of physician professional fulfillment that highlights the important role that institutions plan in supporting physicians to be well.

Stanford Professional Fulfillment Model. Used with permission.

The Stanford WellMD center has developed a model of physician professional fulfillment that highlights the important role that institutions plan in supporting physicians to be well.

While individuals can adopt and strengthen practices to increase personal resilience, institutions must build a culture that supports wellbeing and ensure the clinical environment is designed to optimize efficiency and minimize the clerical work that drains the joy from patient care.

The CHOP Physician Well-being initiative has been at the forefront of this national movement through our involvement in the Stanford Physician Wellbeing Academic Consortium, of which we were one of the founding members. In partnership with Stanford, we administered the Physician Wellness Survey in 2017 and 2019 to our subspecialty and hospital-based physicians, and in 2018 to those in our care network. In response to the survey data, the hospital has invested in at-the-elbow EPIC training for physicians, pilots of scribes and centralized prior authorization support, and bimonthly faculty gatherings to foster a greater sense of community. Well-being leads are active in the majority of divisions, identifying unique pain points at the local level and undertaking improvement projects to address them. Projects have ranged from attempting to reduce the volume of EPIC in-basket messages to developing physician interest groups to help physicians get to know each other better. We have found that divisions that engaged in well-being improvement were more likely to reduce burnout and improve professional fulfillment.

The well-being of healthcare professionals is a complex issue that will require creative thinking and innovative approaches. There are no easy answers, and it can be daunting to consider the myriad forces at play, many of which are outside of our control. So how can we act today to create change?

I encourage you to take a few minutes today to take stock of the least value-added aspect of your day or week or month and consider ways to reduce, eliminate, delegate, or outsource this task. Use the recovered time—even if it just 20 minutes—to do something that nourishes you or nourishes a sense of connection in your life, whether it is taking a few mindful breaths, spending some extra minutes one-on-one with your child, adding an exercise session to your week, or having lunch with a friend. These small changes won’t fix the healthcare system, but may add to your coping reserve, allowing you to feel more able to thrive despite inevitable challenges.

If you notice a colleague struggling, consider making time to sit down with them and ask how they are doing. Avoid the temptation to try to fix things, and instead be a compassionate listener. Ask what they love about their job and what feels overwhelming. Ask what small change they could make to open up some time to recharge. Offer to check in with them on a regular basis; connection and community are themselves antidotes to burnout.

Many of you have leadership roles, or sit on committees either in your own practice setting or as part of national organizations. Can you introduce physician well-being as a discussion point, either independently or as relates to other operational or policy issues? Can well-being be included as a metric or balancing measure in proposed changes that could impact physicians?

If you have the passion and bandwidth, consider initiating a process of assessment and improvement of well-being where you work. This could include measuring rates of burnout and professional fulfillment, convening focus groups to determine what needs to be improved, designing tests of change targeting the drivers of dissatisfaction in your group, or creating opportunities for your colleagues to gather and get to know each other. Together, we can ensure the lens of medicine stays focused on the joy of caring—for children, families, and each other. Have ideas or want to get involved? Email us.

Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, Boone S, Tan L, Sloan J, Shanafelt TD. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014 Mar;89(3):443-51

Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, Trockel M, Tutty M, Satele DV, Carlasare LE, Dyrbye LN. Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction With Work-Life Integration in Physicians and the General US Working Population Between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019 Sep;94(9):1681-1694.

Freudenberger HJ. Staff Burn‐Out. Journal of Social Issues 1974 Vol: 30 (1):159-165.

Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of organizational behavior. 1981 Apr;2(2):99-113.

Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2017 Jan 1 (Vol. 92, No. 1, pp. 129-146).

Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, Prgomet M, Reynolds S, Goeders L, Westbrook J, Tutty M, Blike G. Allocation of Physician Time in Ambulatory Practice: A Time and Motion Study in 4 Specialties. Ann Intern Med. 2016 Dec 6;165(11):753-760.

Contributed by: Miriam Stewart, MD

Categories: Children's Doctor Spring 2020