Your Generosity. Their Future.

Your generosity fuels discovery and transforms the lives of children and their families, today and for generations to come. From donations and planned gifts to joining one of our many inspiring events, there are so many ways you can help.

Drawing on the Community

Struggling from a shortage of phlebotomists and recognizing high unemployment rates in the surrounding area, CHOP took matters into its own hands and started a paid eight-week training program with a job offer at the end.

Your impact

All in one place

Genetic testing revealed that Audrey had a rare condition called Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. With so many different areas of the body potentially affected, a child needs to be seen by multiple specialists, and CHOP is just the place to help. Donor support helps make it possible.

Breathing new life into CPR

A day in the life of a facility dog

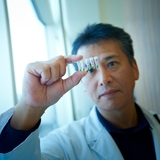

CHOP Biobank: A reservoir of knowledge

Embedded in communities for better healthcare accessibility and creating the largest healthcare network in the U.S.

Established to enable healthier families, stronger schools, thriving neighborhoods and successful businesses

Dedicated research space equipped to make the next great breakthroughs for all children

Newborns Get New Answers

CHOP's Baby Eagle program helps families get answers more quickly with rapid genomic testing that aims to expand and accelerate diagnostics for genetic conditions. Generous donors help make this life-changing work possible.

Join us as we save lives and advance pediatric healthcare

Parkway Run & Walk, presented by Citadel Credit Union

Join us this September for the Parkway Run & Walk and help us conquer cancer!

Carousel Ball

The Carousel Ball brings together more than 800 of the region’s greatest philanthropists, corporate leaders and patient families for an evening of inspirational storytelling and immediate impact on the patients we serve.

CHOP Buddy Walk®

Join us in October to support breakthrough care and brighter futures for individuals with Down syndrome.

Raise funds for CHOP

Fundraise for CHOP in your community! Host an event, start an online fundraiser, or come up with your own creative idea. There is no limit to the ways you can support the children we serve.

Volunteer Services

The volunteers who donate their time play an important role in the experience of our patients and families.

Corporate Charitable Partnerships

Generous support from corporations that share our commitment to children’s well-being enables CHOP to serve a growing community in the Philadelphia region and save lives worldwide. Here’s how corporations and foundations can join forces with CHOP.

Make a Gift to CHOP in Your Will or by Beneficiary Designation

A gift to CHOP in your will or trust, or by beneficiary designation, can ensure happy, healthy tomorrows for children everywhere.

Driven to discovery

At CHOP, we are solving the previously unsolvable. Fueled by an endless curiosity and generous philanthropy, we are finding new ways to create healthy outcomes for every child we serve.

For inquiries about:

- Making a gift

- Gifts you have already made

- Changing your fundraising communication preferences

- Other general questions