Measles, Mumps and Rubella (MMR): The Diseases & Vaccines

Questions about MMRV vaccine?

MMRV is a combination vaccine that includes the MMR vaccine and the chickenpox (varicella) vaccine. In this short video, Dr. Lori Handy describes the considerations for families related to MMRV or separate MMR and chickenpox vaccines when it is time for their children to be protected against these four diseases. (Video length: 2.5 minutes)

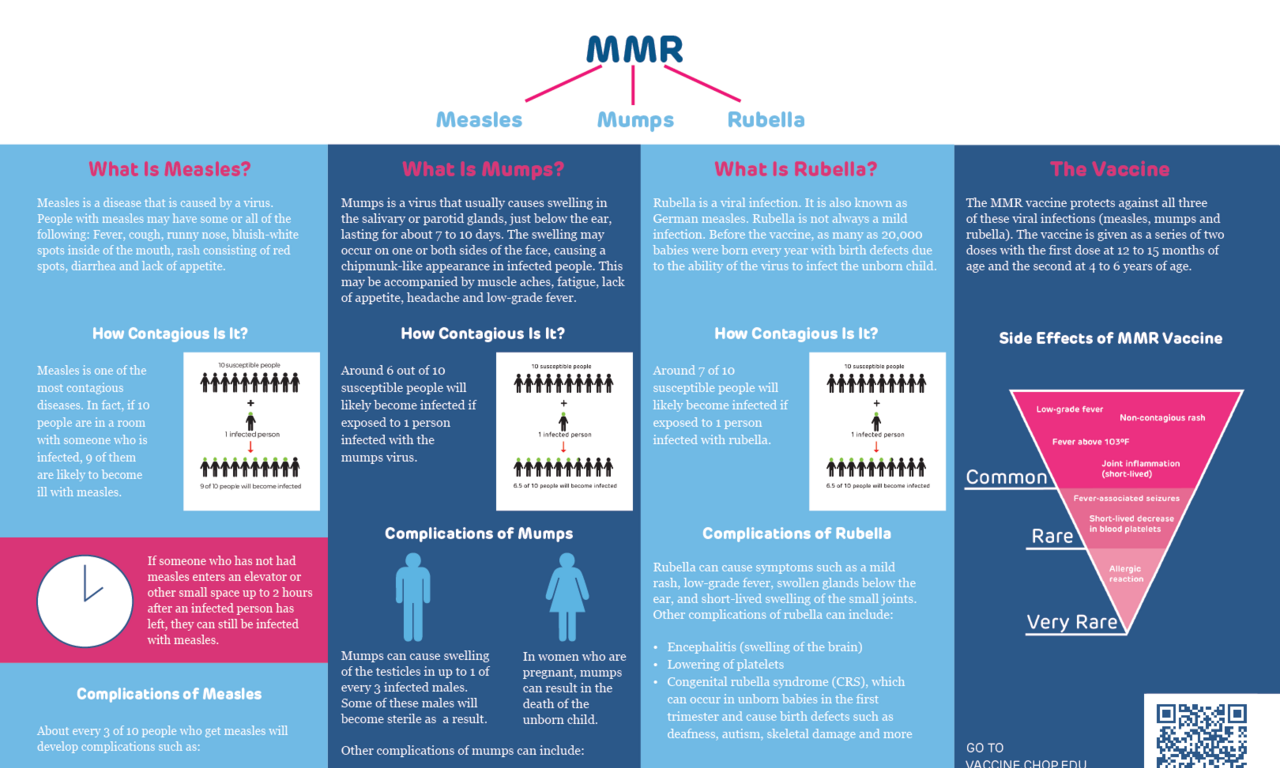

Measles, mumps and rubella are all diseases caused by viruses. Each of these diseases were widespread in the past. Vaccines changed that.

Vaccines to prevent each of these diseases were first developed in the 1960s. The three vaccines were combined to form the MMR vaccine in 1971.

The diseases

Measles

The face of measles

In 1991 the city of Philadelphia was in the grip of a measles epidemic. An epidemic occurs when an area or group of people are experiencing higher numbers of cases than typical.

The 1991 Philadelphia epidemic was centered among two religious groups that refused immunizations. Several children in these groups got measles. They developed the most common features of measles:

- high fever

- a red, raised rash that started on the face and spread to the rest of the body

- "pink eye"

For some of the children, the disease was much worse. Six children in these religious groups and three children in the surrounding community died from measles.

Measles was eliminated from the U.S. in 2000 due to effective use of vaccine. However, small numbers of cases occurred each year. Some years were worse than others, but over time, outbreaks have gotten larger. For example, in 2019, almost 1,300 cases were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Of those, 128 people were hospitalized and 61 experienced complications like pneumonia and encephalitis (inflammation of the brain). Between 2000 and 2024, three people in the U.S. died from measles. Unfortunately, in 2025, large numbers of cases led to three deaths from measles by May. The reason outbreaks have been increasing in size and severity is because more parents are choosing not to vaccinate their children. Scientists and public health officials often call measles the “canary in the coal mine” because it is the first to return when immunization rates drop.

What is measles?

Measles is a disease that is caused by a virus. People with measles may have some or all of the following:

- A fever that gradually goes up to 103°-105° Fahrenheit.

- Cough, runny nose, pink eye.

- Raised, bluish-white spots inside the mouth (called Koplik spots).

- A rash with red spots that are raised in the middle. The rash begins at the hairline and moves to the face and neck before spreading downward and outward to the rest of the body.

- Diarrhea.

- Lack of appetite.

Watch as Drs. Paul Offit and Katie Lockwood from CHOP talk about measles, its symptoms, complications, how it’s spread, what doctors worry about, and more.

How does measles spread?

Measles viruses are spread in the small respiratory droplets from coughing and sneezing. If a susceptible person breathes in these droplets or touches an infected surface and then puts their hand in their mouth or nose, they are likely to get measles. Small droplets containing measles virus can also hang in the air for a couple of hours. This means that someone does not need to come face to face with an infected person to get measles.

How contagious is measles?

Measles is the most contagious infectious disease. If 100 susceptible people are in a room with someone with measles, 90 to 100 of them will also get measles.

People do not need to even be in the same room with an infected person to get measles. Small respiratory particles with the virus can hang in the air for up to two hours after a person coughs or sneezes. This means if someone who has not had measles enters an elevator or other small space up to two hours after an infected person has left, they can breathe in the virus-containing particles and be infected without ever seeing the infected person.

Are there complications from measles infections?

Yes. Measles infections affect a person’s immune system in two ways. First, they cause a temporary immune suppression. This immune suppression increases a person’s risk of getting other infections in the weeks after having measles. Second, measles attacks cells of the immune system, known as memory cells. This attack on immunologic memory means that the person will become susceptible to infections that they were protected against before they got measles. This is called immune amnesia. It can take years for a person to regain the immune protection they lost from this effect of measles.

In addition, about 3 of every 10 people who get measles will develop other complications. Some of these may seem minor, but some can be devastating. Complications can include:

- Ear infection

- Pneumonia (infection of the lungs)

- Encephalitis (swelling of the brain)

- Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis or SSPE (a disease that causes worsening neurological deterioration and death)

- Hemorrhagic measles (a version of measles that causes seizures, delirium, difficulty breathing and bleeding under the skin)

- Blood-clotting disorder

Some of these complications are fatal.

SSPE is particularly devastating for a few reasons. First, people appear to recover, but the virus continues to reproduce in their brain. Symptoms may not appear until years after the infection. Second, SSPE results in certain death. Death follows a period of increasing neurological decline. Early symptoms can be a drop in grades, forgetting words or other information, changes in personality or outbursts. Over time, the person will lose muscle control and may experience seizures. While some treatments may slow progression, the disease invariably results in death.

Measles infections during pregnancy can cause miscarriage, preterm delivery, or delivery of babies with a low birth weight.

People who are immune compromised are at risk of having prolonged and severe illness if they get measles.

What if I suspect measles?

Call your healthcare provider and mention your concern. Because measles is so contagious, providers typically have patients who might have measles avoid the waiting room. This may mean they will suggest you enter through another entrance, have a car visit, or call when you arrive, so you can be given a mask and taken right to an exam room. It is particularly important to avoid the waiting room because often infants too young to be vaccinated are present.

Mumps

The face of mumps

Mumps used to be the most common cause of meningitis in children. Meningitis is a swelling of the lining of the brain and spinal cord. Virtually all children recovered from meningitis caused by mumps, but some were left permanently deaf. This happened so often that mumps was the most common cause of deafness that developed after birth in the United States. All of this changed once we had a vaccine to prevent mumps.

The vaccine was developed by Dr. Maurice Hilleman. Dr. Hilleman had been working to create a vaccine for mumps, when his own daughter, Jeryl Lynn, became ill with mumps. She was 5 years old. When Dr. Hilleman realized his daughter had mumps, he swabbed her throat, took the sample to the lab and grew mumps virus. It was the virus that grew from his daughter’s sample that was eventually used to make the vaccine. For this reason, the vaccine strain of virus is called the “Jeryl Lynn strain.”

Cases of mumps occur each year in the U.S. In the 2020s cases have numbered between 300 and 400 each year. But large outbreaks can occur and lead to thousands of cases.

What is mumps?

Mumps is a virus that usually causes swelling in the salivary glands, most specifically the parotid glands. The parotid glands are located just below the ear. The swelling can occur on one or both sides of the face. It causes the cheeks of infected people to look like those of a chipmunk. People with mumps may also have achy muscle, fatigue, lack of appetite, headache and low-grade fever. They are usually ill for seven to 10 days.

Many mumps infections are mild, but not all are. Mumps can infect the testicles, causing a disease known as orchitis. This happens in up to 1 of every 3 infected males. Some men with orchitis become sterile, meaning they are unable to father children. Mumps virus can also infect the ovaries, causing oophoritis, which can lead to sterility in women. Mumps during pregnancy can also be dangerous. In some cases, these infections of pregnancy result in the death of the unborn child.

Rubella

The face of rubella

Rubella was identified in the early 1800s, but it took until 1941 for its most significant damage to be realized. Dr. Norman McAlister Gregg, an Australian eye doctor, made a curious observation. He noticed that many of his patients were infants born with cataracts and blindness. He heard some of the mothers discussing rubella infections during pregnancy. He and others explored this idea of a link between rubella during pregnancy and health issues in the infants. These doctors and scientists confirmed that rubella could permanently damage the developing fetus.

Rubella is mostly considered a mild disease for children. It can cause a light, mild rash on the face of infected children. Some children also develop swelling of the lymph glands behind the ear. But as Dr. Gregg and others found, the biggest concern is when rubella occurs during pregnancy. In these cases, the children are born with congenital rubella syndrome (CRS).

Rubella was eliminated from the U.S. in 2004. Less than 10 cases occur in the U.S. each year. But rubella continues to occur in other parts of the world. Because it is so devastating during pregnancy, it is important to ensure that we have high levels of immunity in the U.S. This will prevent the virus from spreading to pregnant women and harming their unborn babies.

What is rubella?

Rubella is a viral infection. It is also known as German measles. Rubella infection of children causes a mild rash on the face and swelling of glands behind the ear. In some cases, it also causes a short-lived swelling of small joints (like the joints of the hand) and low-grade fever. Children virtually always recover from rubella without consequence.

But rubella is not always a mild infection. If a woman is infected during pregnancy, the effects on her unborn child can be deadly. Before the rubella vaccine as many as 20,000 babies were born every year with birth defects because they got infected with the virus in the womb during their mother’s infection. Children were most affected if the maternal infection occurred during the first trimester of pregnancy. In this scenario about 85 of 100 babies were permanently harmed. Rubella virus can cause blindness, deafness, heart defects or mental deficits in infants whose mothers were infected early in pregnancy.

Rubella parties

The rubella vaccine became available in 1969. Before that time, rubella parties were recommended to ensure that young girls had rubella before they were old enough to become pregnant. Today, the rubella vaccine ensures that girls are protected before they reach the age to become pregnant. The vaccine has also allowed us to eliminate rubella from the U.S., so the virus no longer spreads in communities. This further ensures that babies today are not born with congenital rubella syndrome in the U.S. Unfortunately, rubella and CRS still occurs in some other parts of the world.

The vaccines

MMR vaccine

The MMR vaccine contains three vaccines that were combined in 1971. The vaccines protect against three viral infections: measles, mumps and rubella. MMR vaccine is given as a series of two doses. The first dose is usually given at 12 to 15 months of age, and the second dose is usually given between 4 and 6 years of age.

Watch as Dr. Offit talks about the safety of the MMR vaccine in the short video below, part of the series Talking About Vaccines with Dr. Paul Offit.

While the MMR vaccine is the only way to be protected against measles, mumps and rubella, this section describes each vaccine component separately.

Measles vaccine

How is the measles vaccine made?

The measles vaccine is a live, "weakened" form of natural measles virus. The viruses are "weakened" by growing them in cells that are different from the ones they infect in people. This process is called "cell culture adaptation" (see How Are Vaccines Made?). "Cell culture adaptation" changes natural measles virus, so it does not infect our cells as efficiently when it is given in the vaccine.

Natural measles virus normally grows in cells that line the back of the throat, skin or lungs. Cells are the building blocks of all the different parts of the body, like skin, heart, muscles and lungs. Natural measles virus reproduces itself thousands of times in our cells. The result can be mild or severe disease. We don’t know who will get mild disease and who will get severe disease when they get a natural measles infection. During a measles infection, the virus that is made in the infected person’s cells is passed on to the next person unchanged.

The process of "cell culture adaptation" changes all of that. Natural measles virus was first taken from someone infected with measles. The virus was then "grown" in cells taken from chick embryo cells. By repeatedly growing the virus in chick embryo cells, it became less and less able to grow in human cells.

When this adapted virus is used in the vaccine, it reproduces very poorly. This results in two important outcomes of vaccination:

- No one will get severe disease. We have changed our odds. With natural infection some people having mild illness, and some will have severe illness and complications. With vaccination no one will have severe illness or complications from measles. In fact, many vaccinated people don’t even feel sick after getting the vaccine. This is because the measles vaccine virus reproduces itself probably fewer than 20 times (compared with the thousands of times after natural infection).

- Importantly, the measles vaccine virus still reproduces itself enough to generate immunity against measles. Immunity from the measles vaccine is life-long. (See how vaccines work.)

The effectiveness of the measles vaccine has been dramatic. The first measles vaccine became available in the United States in 1963. Each year before we had a vaccine in the U.S.:

- About 3-4 million people were diagnosed with measles

- About 48,000 were admitted to the hospital

- About 500 people died every year

We eliminated measles by the year 2000. Most years since then, only a few hundred cases occurred. But we have started to see larger outbreaks, especially as fewer parents opt to protect their children with the MMR vaccine. In 2025, large outbreaks have caused several thousand cases of measles. Many of these cases have been unreported, so official reports suggest a brighter picture than reality. Usually, about 1 person dies for every 1,000 cases of measles. By early May, three deaths had occurred. Two of these deaths were in previously healthy, school-aged girls. The three deaths in early 2025 equal the number of measles deaths in the U.S. between 2000 and 2024.

What are the side effects of the measles vaccine?

The MMR vaccine can cause soreness in the local area of the shot and occasionally a low-grade fever. Sometimes people will develop a fever greater than 103 degrees Fahrenheit about five to 12 days after receiving the shot. This fever is due to the measles part of the MMR vaccine. About 1 of every 3,000-4,000 children will develop a fever that increases rapidly and causes a fever-associated seizure. This is called a febrile seizure. While febrile seizures, are scary, they do not cause long-term harm. (You can find out more about fever and this type of seizure on the Q&A, Infectious Diseases and Fevers: What You Should Know.”)

Some people develop a mild, measles-like rash about seven to 12 days after getting the MMR vaccine. People with this reaction can still get the MMR vaccine in the future. Those with measles rash after getting the vaccine are not contagious to other people.

Because the measles vaccine is made in chick embryo cells, it was once thought that people with egg allergies should not receive the MMR vaccine. This is no longer the case. Studies showed that even people with severe egg allergies can get the MMR vaccine without consequence.

Rarely, the MMR vaccine can also cause a short-lived decrease in the number of platelets that circulate in the body. Platelets are cells that help the blood clot after an injury. This reaction is called thrombocytopenia. It can be caused by either the measles or rubella part of the MMR vaccine. Thrombocytopenia occurs in about 1 of every 40,000 people who get the MMR vaccine. It has never been fatal. Thrombocytopenia occurs more often after natural infection. Natural measles causes about one case per every 20,000 measles infections. Natural rubella causes about one case per every 3,000 rubella infections.

Mumps vaccine

How is the mumps vaccine made?

The mumps vaccine is a live, "weakened" form of natural mumps virus. The viruses are "weakened" by growing them in cells that are different from the ones they infect in people. This process is called "cell culture adaptation" (see How Are Vaccines Made?). "Cell culture adaptation" changes natural mumps virus, so it does not infect our cells as efficiently when it is given in the vaccine.

Natural mumps virus normally grows in cells of the salivary glands. Cells are the building blocks of all the different parts of the body, like skin, heart, muscles and lungs. Natural mumps virus reproduces itself thousands of times in our cells. Mumps is usually mild in children, but it can cause males to become sterile if the virus infects their testicles.

Natural mumps virus was first taken from a little girl named Jeryl Lynn Hilleman. Jeryl Lynn was the 5-year-old daughter of Dr. Maurice Hilleman. Dr. Hilleman was a scientist working in the research laboratories of a company named Merck, Sharp & Dohme. He was trying to develop a mumps vaccine when his daughter got mumps, so he took a sample of the virus from her infection. He then "grew" the virus in eggs. By repeatedly growing the virus in hen's eggs, it became less able to grow in human cells.

When this adapted vaccine virus was used in the vaccine, it grew poorly in human cells. The mumps vaccine virus reproduces itself probably fewer than 20 times (compared with thousands of times after natural infection). That is why natural mumps virus causes illness, but mumps vaccine virus doesn't. The good news is that the mumps vaccine virus reproduces enough to induce immunity against mumps. (See how vaccines work.) Over time as mumps has become less common, immunity against mumps has waned, causing outbreaks of mumps on some college campuses. As a result, people involved in outbreaks may be recommended to get a third dose of MMR vaccine. This will strengthen their immunity to mumps.

In addition, as more parents choose not to protect their children with the MMR vaccine, we could see more outbreaks of mumps.

What are the side effects of the mumps vaccine?

The MMR vaccine may cause soreness in the local area of the shot and occasionally a low-grade fever.

Because the mumps vaccine is made in chick embryo cells, it was once thought that people with egg allergies should not receive the MMR vaccine. This is no longer the case. Studies showed that even those with severe egg allergies could receive MMR vaccine without serious consequence.

Rubella Vaccine

How is the rubella vaccine made?

Like the measles and mumps vaccines, the rubella vaccine is a live, "weakened" form of natural rubella virus. The viruses are "weakened" by growing them in cells that are different from the ones they infect in people. This process is called "cell culture adaptation" (see How Are Vaccines Made?). "Cell culture adaptation" changes natural mumps virus, so it does not infect our cells as efficiently when it is given in the vaccine.

Natural rubella virus normally grows in cells that line the back of the throat. It also grows in fetal cells. That is why it can cause congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) when a woman is infected with rubella during pregnancy. Cells are the building blocks of all the different parts of the body, like skin, heart, muscles and lungs. Natural rubella virus reproduces itself thousands of times in throat and fetal cells. Rubella is usually mild in children, but it can be deadly to an unborn baby if their mother is infected during pregnancy.

Natural rubella virus was first taken from someone infected with rubella. The virus was then "grown" repeatedly in human embryo fibroblast cells in the lab. Fibroblast cells are the cells needed to hold skin and other connective tissue together. These cells were first obtained from an elective termination of one pregnancy in England in the early 1960s. These same embryonic cells have continued to grow in the laboratory and are used to make rubella vaccine today. To find out more about how the same cells can be used so many years later, check this article that describes cell passage, a common laboratory technique (see the section titled, “No additional fetuses needed”).

By repeatedly growing rubella virus in human embryo fibroblast cells, it became less able to grow in human cells that lined the back of the throat.

When this adapted vaccine virus was given as a vaccine, it grew very poorly. The rubella vaccine virus reproduces itself probably fewer than 20 times (compared with thousands of times after natural infection). That is why natural rubella virus causes illness, but rubella vaccine virus doesn't. The good news is that the rubella vaccine virus reproduces enough to induce immunity against rubella that is lifelong. (See how vaccines work.)

We have good evidence of how weakened the rubella vaccine virus is compared with natural rubella virus. The MMR vaccine has been mistakenly given to pregnant women during their first trimester more than 1,000 times. No child born to these mothers ever had congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) or its associated symptoms. On the other hand, of 1,000 women infected with natural rubella infection during the first trimester, 850 babies will have birth defects resulting from congenital rubella syndrome (CRS).

Two purposes of rubella vaccine

Rubella vaccine serves two important purposes:

- Vaccination of girls and boys protects them from rubella, which also decreases the spread of rubella in our communities.

- Vaccination of girls protects any future unborn children they may have. If they can’t get rubella during pregnancy, their unborn children cannot get congenital rubella syndrome.

What are the side effects of the rubella vaccine?

Some people experience soreness in the local area of the shot and a low-grade fever. Some may also develop a mild rash that is not contagious to others.

The rubella vaccine can also cause arthritis (swelling and pain in the joints) in some women. This effect typically occurs in vaccine recipients older than 14 years. The arthritis is typically short-lived and doesn't cause permanent harm. Because the evidence for chronic arthritis is inconclusive, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) has indicated that more studies should be completed and the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program (VICP) includes chronic arthritis the develops between 7 and 42 days after receipt of a rubella-containing vaccine as a compensable injury. The rubella vaccine is also an extremely rare cause of short-lived arthritis in young children.

Other questions you might have

Should my child get vaccinated early during a measles outbreak?

Two doses of MMR vaccine are recommended. The first at 12-15 months of age. The second at 4-6 years of age. These ages can be changed in certain situations, including for international travel and during outbreaks. Families should talk with their child’s healthcare provider to consider the following when making decisions about the right time to vaccinate.

The biology of dose one

In certain situations, babies can get the MMR vaccine as early as 6 months of age. A few considerations are important related to this decision:

- Maternal antibodies — One of the reasons the recommendation in the U.S. is around 1 year of age is because babies typically have some protection against measles from maternal antibodies. These are antibodies they got before birth through the placenta. The level of protection will vary based on mom’s antibody levels, whether the baby was full-term, and the baby’s current age. Mothers who were vaccinated will generally have lower antibody levels than those who had measles infections. If the baby was born early (preterm), they may have lower antibody levels because most maternal antibodies are transferred in the last four weeks of pregnancy. Finally, as that baby gets older, maternal antibodies levels will decrease. Some estimates suggest that 90% of babies may lack detectable measles antibodies by 6 months of age.

- Baby’s immune system — While 93 to 95 of 100 babies will be protected after 1 dose of vaccine at 1 year of age, these numbers are lower when babies are vaccinated earlier. It’s estimated that 85 to 90 of 100 will be protected if vaccination occurs before 1 year of age. In addition, babies vaccinated at 6 months of age may have lower levels of measles antibodies compared with those vaccinated at 9 or 12 months of age. Even when they get another dose of measles-containing vaccine at an older age, their antibody levels tend to be lower compared with those of people vaccinated at an older age. This lower immune response does not apply to T cell responses. Importantly, the antibody levels are usually still high enough to be protective, but parents should still be aware.

- Additional dose — Babies who get a dose of MMR vaccine at 6 months of age are still recommended to get two additional doses after 1 year of age.

The biology of dose two

The second dose of MMR is generally recommended around the start of school, but it can be given earlier. The main reason for the second dose is to protect more people. First, some people miss the first dose, so this provides another opportunity for protection. Second, more people will develop immunity after the second dose. After two doses about 97 to 99 of 100 people will be protected against measles compared with 93 to 95 of 100 after one dose.

People who had one dose will be likely to have a boost in their immune response, but the main reason for the second dose is to protect more people rather than to boost immunity in those who were vaccinated previously.

Outbreak setting and risk for exposure

While MMR vaccination rates have decreased in recent years, many communities throughout the U.S. still enjoy high levels of community immunity. When community immunity is high, even unprotected people are safer. For example, every year cases of measles are diagnosed when infected travelers come into the U.S. after being exposed to measles in other countries. Most of the time, these cases do not result in outbreaks. This is because so many people in the community are immune.

For this reason, families and healthcare providers discussing early vaccination should consider the likelihood of the infant being exposed to measles. If a local outbreak is occurring, public health officials may recommend that babies get vaccinated early. If an infant will be traveling to an area of the U.S. with an outbreak or if they will be traveling internationally to a region where measles continues to circulate, vaccination is likely to be warranted. However, if no local outbreaks are occurring and the child will not be traveling or exposed to someone who has been in an area with an outbreak, the family and healthcare provider may decide to continue monitoring and revisit the decision if something about the situation changes.

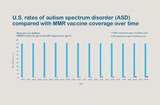

Does the MMR vaccine cause autism?

The short answer to this question is no. Two dozen studies have been done without finding any link. These studies looked at the question in different ways. The studies were also completed by different research teams. They evaluated multiple populations living on different continents and over different lengths of time. No link has been found.

In the U.S. it is true that rates of autism have been increasing. But a comparison of the increases in autism with use of MMR vaccine provides important context. As this chart shows, many, many more children have gotten the MMR vaccine (blue bars) compared with the number diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD; pink bars). Since 2000 in the U.S.:

- More than 90 of every 100 children got the MMR vaccine.

- Rates of autism have increased from less than 1 in 100 to about 3 in 100.

To find out more about the history of this concern and what we know about the causes of autism, check our “Vaccines and Autism” webpage.

Why do children have to get two doses of MMR vaccine?

A second dose of MMR vaccine was recommended in the early 1990s. Two doses are recommended for a few reasons:

- Outbreaks of measles swept across the United States in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Most of the people who got measles during these outbreaks were adolescents and young adults. An investigation of what went wrong found that many of the people who got measles had never been immunized. So the main reason for recommending a second dose of MMR was to give people two chances to get this vaccine.

- A second dose of MMR vaccine also ensures that more children develop a protective immune response against measles. About 93 to 95 of every 100 people will be protected against measles after one dose of MMR. But a second dose increases that number to about 97 to 99 of 100 people being protected against measles. Creating immunity in more people, even if it is only a few more people of every 100, is important when we are trying to protect against a disease as highly contagious as measles.

- The additional dose of MMR vaccine also helps decrease outbreaks of mumps. Mumps outbreaks have been occurring on college campuses in recent years. The ACIP recommended 2 doses of MMR to increase protection against mumps for school-aged children in 2006. This was also recommended for adults at increased risk for mumps, such as college students, health care providers, and international travelers. In 2018, a third dose of MMR vaccine was approved for those at increased risk for mumps during outbreaks.

- The second dose of MMR vaccine also increases the number of people protected against rubella.

Should teenagers and adults get the MMR vaccine?

The MMR vaccine should be given to any teenager or adult who has not had two doses of the vaccine or natural measles, mumps and rubella infections.

Do people older than 65 years of age need MMR vaccine during an outbreak of measles, mumps or rubella?

Not typically. Each of these diseases was widespread before vaccines were available. As such, most older adults had these diseases as children. Anyone born before 1957 is considered to be immune from each of these diseases even if they do not recall having them. Those born between 1957 and 1967 who were naturally infected do not need a dose of vaccine. Those who received vaccines that were available between 1963 and 1967, before the 1968 vaccine was available, should receive one dose of MMR as those earlier vaccines were not as effective.

Healthcare providers are at increased risk for exposure to these diseases, so even those born before 1957 often require vaccination. Likewise, others at increased risk, such as during international travel, may be recommended to get vaccinated.

If you have questions about your vaccination status or whether you should get the MMR vaccine, talk to your healthcare provider. They will be able to offer more personalized guidance because they have the benefit of your medical history, current health and potential risk factors.

Is it OK for a 1-year-old to get the MMR vaccine if mom is pregnant or someone in the home is immune compromised?

Yes. The MMR vaccine can be given to children who live with pregnant women or immune-compromised people. While the MMR vaccine contains live measles, mumps and rubella viruses, the viruses are weakened by “cell-culture adaptation” (see the section of this page about how these vaccines are made). Studies have shown that these adapted viruses are not usually transmitted from the vaccine recipient to others. Even if the virus was transmitted, it is too weak to cause harm.

Is there a test to prove that the MMR vaccine has worked in an individual?

While there is a blood test, doctors will typically recommend receipt of the vaccine rather than prescribing the blood test. This is done for a few reasons. First, a second dose of vaccine will not harm the person and will boost any existing immunity. Second, if the test comes back negative, the person will need to get vaccinated. This means a second needle and a second appointment. Finally, the cost of the vaccine is likely to be similar to that of the blood test. So if a vaccine is then necessary, the overall cost will be higher to cover the test and the vaccine.

Your healthcare provider can help you determine if it makes sense to get the test or the vaccine based on your medical history, current health, and any risk factors.

What should I do if my child did not get MMR vaccine, and we will be traveling internationally to a place where measles has been reported?

Parents who will be traveling abroad with infants should discuss their trip with the child’s healthcare provider or with a provider at a travel clinic as soon as possible. This will allow enough time to ensure that the child receives any recommended vaccines based on the travel itinerary and the child’s age. Find out more about preparing your entire family for international travel on our “Vaccine Considerations for Travelers” webpage.

Is the MMR vaccine available as individual components?

Individual components of MMR vaccine are not available in the U.S. The MMR vaccine provides several benefits over having three different vaccines:

- Fewer shots

- Fewer office visits

- Less time to be susceptible to these three diseases (measles, mumps and rubella), particularly because they would need to be separated by at least 28 days between each

- Lower chance for vaccine administration errors

Since people may sometimes only need one of the components, they may worry about getting the other vaccines that are not needed at that time. The good news is that extra doses of vaccine are generally considered to be safe. The extra dose will boost any existing immunity in the same manner as an exposure in the community would.

Can I get measles or rubella from a rash that develops in someone who got the MMR vaccine?

No. Measles and rubella vaccines can cause a mild rash. But neither measles nor rubella vaccine viruses are spread by touching the rash. You could only transmit them to others who are susceptible if you are sick with the diseases. Likewise, most people are already immune because they previously had the diseases or were vaccinated. However, if you are unsure about your immunity, check with your healthcare provider.

Relative risks and benefits

Do the benefits of MMR outweigh its risks?

Measles

Measles was eliminated from the United States in 2000. Small numbers of cases continued to occur each year, but larger outbreaks have been occurring more recently. Between 2000 and 2024, three people in the U.S. died from measles. Unfortunately, in 2025, thousands of cases led to three deaths from measles by May 2025. The reason outbreaks have been increasing in size and severity is because more parents are choosing not to vaccinate their children.

While most people recover from measles, they are miserable while infected and other effects are troublesome. For example, measles causes immune amnesia, leaving people susceptible to infections they used to be protected against even after they recover. Measles can also cause several severe complications, like pneumonia (infection of the lungs) and encephalitis (swelling of the brain). The virus remains in the brain of a very small number of people and causes a fatal disease called sub-acute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE). SSPE often occurs years after the person had measles.

Mumps

Mumps virus can infect the brain and cause permanent deafness. Cases of mumps occur each year in the U.S. In the 2020s cases have numbered between 300 and 400 each year. But large outbreaks can occur and lead to thousands of cases. Many recent outbreaks have occurred on college campuses.

Rubella

Rubella was eliminated from the U.S. in 2004. Fewer than 10 cases occur in the U.S. each year. But rubella continues to occur in other parts of the world. Because it is so devastating during pregnancy, it is important to ensure that we have high levels of immunity in the U.S. This will prevent the virus from spreading to pregnant women and harming their unborn babies.

Each of these diseases can cause harm or death. The MMR vaccine does not cause serious side effects. So the benefits of the MMR vaccine outweigh its risks.

Disease risks

Measles

- Fever, conjunctivitis ("pink eye"), and a red, pinpoint rash that starts on the face and spreads to the rest of the body

- Pneumonia (infection of the lungs)

- Encephalitis (inflammation of the brain)

- Rarely, subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE)

- Death

Mumps

- Swollen parotid glands

- Meningitis (inflammation of the lining of the brain and spinal cord)

- Deafness

- Orchitis (swelling of the testicles)

- Miscarriage during pregnancy

Rubella

- Mild rash on the face, swelling of glands behind the ear

- Occasionally short-lived swelling of small joints (like the joints of the hand)

- Low-grade fever

- Congenital rubella syndrome when women are infected early during pregnancy (85 of 100 babies of women infected during first trimester)

Vaccine risks

- Soreness at the injection site.

- Low-grade fever for most; for some higher fever(>103 degrees Fahrenheit). If fever rises rapidly, a febrile seizure may occur. While scary, this type of seizure does not cause harm or lead to a permanent seizure disorder. Fever from this vaccine typically occurs between five to 12 days after receipt of vaccine.

- Rash.

- Temporary decrease in platelets, cells that help our blood clot (called thrombocytopenia).

- Short-lived arthritis (mainly in adult recipients).

References

Books

Orenstein WA, Offit PA, Edwards KM, and Plotkin SA. Measles vaccines in Plotkin’s Vaccines, 8th Edition, 2024, 629-663.

Orenstein WA, Offit PA, Edwards KM, and Plotkin SA. Mumps vaccines in Plotkin’s Vaccines, 8th Edition, 2024, 711-735.

Orenstein WA, Offit PA, Edwards KM, and Plotkin SA. Rubella vaccine in Plotkin’s Vaccines, 8th Edition, 2024, 1025-1056.

Websites

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Measles Cases and Outbreaks.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mumps Cases and Outbreaks.

Reviewed by Paul A. Offit, MD, on June 26, 2025