Case

A 20-month-old previously healthy male presents to primary care with a history of a few weeks of bruising noted by the parents on the extremities, which are appearing without significant trauma. He has not had any gingival bleeding or epistaxis, and no blood has been noted in his diapers. He presents today because of a red, pinpoint rash on his diaper creases and belly that has been spreading. The rash is petechial and most pronounced in the inguinal region, but also along the diaper line at the waist and more diffusely throughout the body. He has had no fevers, no weight loss, no change in appetite or activity. Physical exam is remarkable for the lack of other findings beyond the bruising, particularly of the extremities with some raised bruises of the anterior lower extremities and diffuse petechiae. He has no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. There is no family history of any bleeding disorders, and he has not had a previous history of bleeding problems.

Discussion

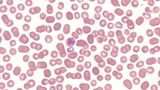

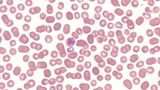

A CBC was normal except for a platelet count of 5K. An immature platelet fraction was elevated at 22 percent and there were giant platelets present on review of the peripheral smear (see Figure 1). The hemoglobin was 11.1 gm/dL, the WBC was 10.1/mcL with a normal differential, and there were no white cell abnormalities on review of the smear. The differential of petechial rash in a well toddler is broad, but when combined with sudden appearance of bruising, it becomes more limited to include non-accidental trauma, Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), and immune thrombocytopenia. When screening labs and history reveal an isolated thrombocytopenia, there is only one diagnosis that is most likely: immune thrombocytopenia (ITP).

Parents and practitioners are always concerned about malignancy, in particular leukemia, but this is rare in isolated severe thrombocytopenia. In fact, although data is primarily retrospective, examination of large cohorts of patients presenting with leukemia shows that none of them presented with ITP. ITP is an autoimmune process triggered most often by antecedent viral infection or vaccination (MMR vaccine has been most commonly implicated).

Treating the underlying immune dysregulation was the mainstay of prior therapy. Novel therapies, which have recently been FDA-approved in adult chronic ITP management (romiplostim and eltrombopag), target platelet production. Eltrombopag was approved for use in children in 2015.

However, in most children with ITP the risk of bleeding is low, and treatment is rarely needed initially. Seventy-five percent of children will have platelet counts > 100,000 by 3 months from diagnosis, and 85 percent will resolve by 12 months. The changes in our understanding of ITP biology and our better appreciation of the natural history have resulted in a change in the nomenclature to immune thrombocytopenia (not immune thrombocytopenic purpura or idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura), although the acronym remains ITP. The old designation of “acute” ITP is no longer applicable.

Current ITP nomenclature

Duration: Terminology: Newly diagnosed

Duration: ≥ 3 months — Terminology: Persistent

Duration: ≥ 12 months

Terminology: Chronic

Because the majority of these children (97 percent) will not have significant bleeding, the goals are education and identification of those patients who may be at increased risk of significant bleeding complications in order to limit pharmacologic therapy to those few children. This represents a significant shift in practice over the past several years.

Currently, we advocate careful observation for the majority of patients with ITP irrespective of platelet count in the absence of significant bleeding symptoms such as bleeding beyond skin manifestations: significant epistaxis, GI, or GU bleeding. This minimizes medication-related costs and side effects given the lack of evidence that treating all patients decreases the risk of intracranial hemorrhage, which occurs in

Children still require referral to a hematologist for evaluation to confirm the diagnosis, as there are other disorders on the differential, but referral to the emergency department for admission and immediate therapy to increase the platelet count is no longer necessary. In fact, children are often evaluated and released from the ED after counseling, with follow-up within a few days with hematology. That is how this 20-month-old was managed. Important parental counseling includes minimizing risk of head trauma by choosing lower-risk activities and avoiding anti-platelet medications such as aspirin and NSAIDs.

References and suggested readings

Dubansky AS, Boyett JM, Falletta J, et al. Isolated thrombocytopenia in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a rare event in a Pediatric Oncology Group Study. Pediatrics. 1989;84(6):1068-1071.

Cecinati V, Principi N, Brescia L, et al. Vaccine administration and the development of immune thrombocytopenic purpura in children. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(5):1158-1162.

Rodeghiero F, Stasi R, Gernsheimer T, et al. Standardization of terminology, definitions and outcome criteria in immune thrombocytopenic purpura of adults and children: report from an international working group. Blood. 2009;12;113(11):2386-2393.

Neunert CE, Buchanan GR, Imbach P. Intercontinental Cooperative ITP Study Group Registry II Participants. Bleeding manifestations and management of children with persistent and chronic immune thrombocytopenia: data from the Intercontinental Cooperative ITP Study Group (ICIS). Blood. 2013;121(22):4457-4462.

Neunert C, Lim W, Crowther M, et al. American Society of Hematology. The American Society of Hematology 2011 evidence-based practice guideline for immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2011;117(16):4190-4207.

Featured in this article

Specialties & Programs

Case

A 20-month-old previously healthy male presents to primary care with a history of a few weeks of bruising noted by the parents on the extremities, which are appearing without significant trauma. He has not had any gingival bleeding or epistaxis, and no blood has been noted in his diapers. He presents today because of a red, pinpoint rash on his diaper creases and belly that has been spreading. The rash is petechial and most pronounced in the inguinal region, but also along the diaper line at the waist and more diffusely throughout the body. He has had no fevers, no weight loss, no change in appetite or activity. Physical exam is remarkable for the lack of other findings beyond the bruising, particularly of the extremities with some raised bruises of the anterior lower extremities and diffuse petechiae. He has no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. There is no family history of any bleeding disorders, and he has not had a previous history of bleeding problems.

Discussion

A CBC was normal except for a platelet count of 5K. An immature platelet fraction was elevated at 22 percent and there were giant platelets present on review of the peripheral smear (see Figure 1). The hemoglobin was 11.1 gm/dL, the WBC was 10.1/mcL with a normal differential, and there were no white cell abnormalities on review of the smear. The differential of petechial rash in a well toddler is broad, but when combined with sudden appearance of bruising, it becomes more limited to include non-accidental trauma, Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), and immune thrombocytopenia. When screening labs and history reveal an isolated thrombocytopenia, there is only one diagnosis that is most likely: immune thrombocytopenia (ITP).

Parents and practitioners are always concerned about malignancy, in particular leukemia, but this is rare in isolated severe thrombocytopenia. In fact, although data is primarily retrospective, examination of large cohorts of patients presenting with leukemia shows that none of them presented with ITP. ITP is an autoimmune process triggered most often by antecedent viral infection or vaccination (MMR vaccine has been most commonly implicated).

Treating the underlying immune dysregulation was the mainstay of prior therapy. Novel therapies, which have recently been FDA-approved in adult chronic ITP management (romiplostim and eltrombopag), target platelet production. Eltrombopag was approved for use in children in 2015.

However, in most children with ITP the risk of bleeding is low, and treatment is rarely needed initially. Seventy-five percent of children will have platelet counts > 100,000 by 3 months from diagnosis, and 85 percent will resolve by 12 months. The changes in our understanding of ITP biology and our better appreciation of the natural history have resulted in a change in the nomenclature to immune thrombocytopenia (not immune thrombocytopenic purpura or idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura), although the acronym remains ITP. The old designation of “acute” ITP is no longer applicable.

Current ITP nomenclature

Duration: Terminology: Newly diagnosed

Duration: ≥ 3 months — Terminology: Persistent

Duration: ≥ 12 months

Terminology: Chronic

Because the majority of these children (97 percent) will not have significant bleeding, the goals are education and identification of those patients who may be at increased risk of significant bleeding complications in order to limit pharmacologic therapy to those few children. This represents a significant shift in practice over the past several years.

Currently, we advocate careful observation for the majority of patients with ITP irrespective of platelet count in the absence of significant bleeding symptoms such as bleeding beyond skin manifestations: significant epistaxis, GI, or GU bleeding. This minimizes medication-related costs and side effects given the lack of evidence that treating all patients decreases the risk of intracranial hemorrhage, which occurs in

Children still require referral to a hematologist for evaluation to confirm the diagnosis, as there are other disorders on the differential, but referral to the emergency department for admission and immediate therapy to increase the platelet count is no longer necessary. In fact, children are often evaluated and released from the ED after counseling, with follow-up within a few days with hematology. That is how this 20-month-old was managed. Important parental counseling includes minimizing risk of head trauma by choosing lower-risk activities and avoiding anti-platelet medications such as aspirin and NSAIDs.

References and suggested readings

Dubansky AS, Boyett JM, Falletta J, et al. Isolated thrombocytopenia in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a rare event in a Pediatric Oncology Group Study. Pediatrics. 1989;84(6):1068-1071.

Cecinati V, Principi N, Brescia L, et al. Vaccine administration and the development of immune thrombocytopenic purpura in children. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(5):1158-1162.

Rodeghiero F, Stasi R, Gernsheimer T, et al. Standardization of terminology, definitions and outcome criteria in immune thrombocytopenic purpura of adults and children: report from an international working group. Blood. 2009;12;113(11):2386-2393.

Neunert CE, Buchanan GR, Imbach P. Intercontinental Cooperative ITP Study Group Registry II Participants. Bleeding manifestations and management of children with persistent and chronic immune thrombocytopenia: data from the Intercontinental Cooperative ITP Study Group (ICIS). Blood. 2013;121(22):4457-4462.

Neunert C, Lim W, Crowther M, et al. American Society of Hematology. The American Society of Hematology 2011 evidence-based practice guideline for immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2011;117(16):4190-4207.

Contact us

Division of Hematology