A previously healthy 16-year-old girl presents with a 1-month history of increasing sleepiness. Over the last week, she has fallen asleep even while eating, causing her family to fear that she will choke. Once asleep, she is almost impossible to wake up.

She also reports being increasingly hungry, eating things she never previously liked and eating at all hours of the day or evening. She has gained 40 pounds. Her one other complaint is that she has frequent hiccups, which can last for hours.

Discussion: The medical diagnoses to consider in the patient with changing sleep patterns include disorders of sleep such as narcolepsy, or abnormality of the sleep center in the brain. Our patient also presents with hyperphagia (abnormally increased appetite). Hyperphagia is a disorder of satiety (the feeling of being full), which is regulated by an area of the brain called the diencephalon. Finally, our patient also complains of frequent hiccups. While hiccups are most commonly due to irritation of the diaphragm muscle in the brainstem, they can also occur due to disorders of the brainstem.

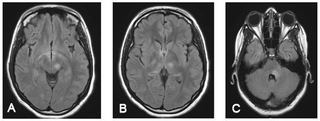

On examination, the optic nerves were abnormal, with pallor of the temporal aspect of the nerves, and reduced vision in her right eye. She reports that two years previously she had an episode of pain with eye movement followed by difficulty seeing colors in the right eye and loss of normal vision. Her symptoms lasted several weeks and improved incompletely. She did not see a doctor for the symptoms. Examination also reveals that our patient has increased reflexes in her legs and some leg stiffness. MRI scans of the brain and spine (see Figure 1) reveal abnormal areas of inflammation in the brain stem and midbrain, the areas of the brain that are involved in sleep regulation, the hunger center, and the region of the brain that can cause hiccups, and she has a long extensive area of inflammation in the spinal cord.

Figure 1: Brain MRI

A: Diencephalic and midbrain lesions; B: Thalamic lesions; C: Lesion in the brainstem surrounding the 4th ventricle

The combination of optic nerve abnormalities, spinal cord abnormalities, and abnormal inflammation in specific areas of the brain stem led to a diagnosis of neuromyelitis optica (NMO). The diagnosis was confirmed by the presence of antibodies that react against aquaporin 4 (or “NMO IgG”).

NMO is a serious immune disorder in which the immune system attacks certain area key areas of the optic nerves, brain, and spinal cord. NMO is a rare disease, with onset in both childhood and in adulthood. NMO appears to be more common in Asian countries, but is being recognized more in multiple world regions. The disease is an acquired autoimmune disease and may occur is isolation or in patients who have other autoimmune diseases such as lupus, Sjogren’s syndrome, or thyroid disease. Treatment with immuno-suppressant medications is essential. Untreated, patients experience recurrent attacks of impairment of the optic nerves, brain, or spine, which can lead to blindness, paralysis, and even death.

NMO is one of a now increasingly recognized group of immune disorders affecting the central nervous system. The classic autoimmune disease of the central nervous system is multiple sclerosis (MS). MS shares several clinical features of NMO, but the two diseases have different biologies and require different treatment strategies. The goal of treatment for NMO and MS is to control abnormal immune activity, without eliminating normal immune control of infection.

Treatments for NMO include corticosteroids, Imuran, and rituximab. Treatments for MS include corticosteroids (only at the time of an attack), interferon-beta, and glatiramer acetate. Newer treatments are on the horizon for both MS and NMO, and treatment trials for children with these diseases will be launched in the near future. Our 16-year-old-patient is now doing well on oral prednisone 10 mg per day and on 6 monthly courses of rituximab.

References and Suggested Readings

Wingerchuk DM, Weinshenker BG. Neuromyelitis optica: clinical predictors of a relapsing course and survival. Neurology. 2003;60(5):848-853.

Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Pittock SJ, Lucchinetti CF, Weinshenker BG. Revised diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica. Neurology. 2006;66(10):1485-1489.

Banwell B, Tenembaum S, Lennon VA, et al. Neuromyelitis optica-IgG in childhood inflammatory demyelinating CNS disorders. Neurology. 2008;70(5):344-352.

Cree B. Neuromyelitis optica: diagnosis, pathogenesis, and treatment. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2008;8(5):427-433.

Dale RC, Brilot F, Banwell B. Pediatric central nervous system inflammatory demyelination: acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, clinically isolated syndromes, neuromyelitis optica, and multiple sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2009;22(3):233-240.

Referral Information

To refer a patient to the Division of Neurology or one of its specialty programs, call 215-590-1719.

A previously healthy 16-year-old girl presents with a 1-month history of increasing sleepiness. Over the last week, she has fallen asleep even while eating, causing her family to fear that she will choke. Once asleep, she is almost impossible to wake up.

She also reports being increasingly hungry, eating things she never previously liked and eating at all hours of the day or evening. She has gained 40 pounds. Her one other complaint is that she has frequent hiccups, which can last for hours.

Discussion: The medical diagnoses to consider in the patient with changing sleep patterns include disorders of sleep such as narcolepsy, or abnormality of the sleep center in the brain. Our patient also presents with hyperphagia (abnormally increased appetite). Hyperphagia is a disorder of satiety (the feeling of being full), which is regulated by an area of the brain called the diencephalon. Finally, our patient also complains of frequent hiccups. While hiccups are most commonly due to irritation of the diaphragm muscle in the brainstem, they can also occur due to disorders of the brainstem.

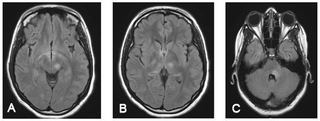

On examination, the optic nerves were abnormal, with pallor of the temporal aspect of the nerves, and reduced vision in her right eye. She reports that two years previously she had an episode of pain with eye movement followed by difficulty seeing colors in the right eye and loss of normal vision. Her symptoms lasted several weeks and improved incompletely. She did not see a doctor for the symptoms. Examination also reveals that our patient has increased reflexes in her legs and some leg stiffness. MRI scans of the brain and spine (see Figure 1) reveal abnormal areas of inflammation in the brain stem and midbrain, the areas of the brain that are involved in sleep regulation, the hunger center, and the region of the brain that can cause hiccups, and she has a long extensive area of inflammation in the spinal cord.

Figure 1: Brain MRI

A: Diencephalic and midbrain lesions; B: Thalamic lesions; C: Lesion in the brainstem surrounding the 4th ventricle

The combination of optic nerve abnormalities, spinal cord abnormalities, and abnormal inflammation in specific areas of the brain stem led to a diagnosis of neuromyelitis optica (NMO). The diagnosis was confirmed by the presence of antibodies that react against aquaporin 4 (or “NMO IgG”).

NMO is a serious immune disorder in which the immune system attacks certain area key areas of the optic nerves, brain, and spinal cord. NMO is a rare disease, with onset in both childhood and in adulthood. NMO appears to be more common in Asian countries, but is being recognized more in multiple world regions. The disease is an acquired autoimmune disease and may occur is isolation or in patients who have other autoimmune diseases such as lupus, Sjogren’s syndrome, or thyroid disease. Treatment with immuno-suppressant medications is essential. Untreated, patients experience recurrent attacks of impairment of the optic nerves, brain, or spine, which can lead to blindness, paralysis, and even death.

NMO is one of a now increasingly recognized group of immune disorders affecting the central nervous system. The classic autoimmune disease of the central nervous system is multiple sclerosis (MS). MS shares several clinical features of NMO, but the two diseases have different biologies and require different treatment strategies. The goal of treatment for NMO and MS is to control abnormal immune activity, without eliminating normal immune control of infection.

Treatments for NMO include corticosteroids, Imuran, and rituximab. Treatments for MS include corticosteroids (only at the time of an attack), interferon-beta, and glatiramer acetate. Newer treatments are on the horizon for both MS and NMO, and treatment trials for children with these diseases will be launched in the near future. Our 16-year-old-patient is now doing well on oral prednisone 10 mg per day and on 6 monthly courses of rituximab.

References and Suggested Readings

Wingerchuk DM, Weinshenker BG. Neuromyelitis optica: clinical predictors of a relapsing course and survival. Neurology. 2003;60(5):848-853.

Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Pittock SJ, Lucchinetti CF, Weinshenker BG. Revised diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica. Neurology. 2006;66(10):1485-1489.

Banwell B, Tenembaum S, Lennon VA, et al. Neuromyelitis optica-IgG in childhood inflammatory demyelinating CNS disorders. Neurology. 2008;70(5):344-352.

Cree B. Neuromyelitis optica: diagnosis, pathogenesis, and treatment. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2008;8(5):427-433.

Dale RC, Brilot F, Banwell B. Pediatric central nervous system inflammatory demyelination: acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, clinically isolated syndromes, neuromyelitis optica, and multiple sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2009;22(3):233-240.

Referral Information

To refer a patient to the Division of Neurology or one of its specialty programs, call 215-590-1719.