What is hypothyroidism?

Hypothyroidism is a common endocrine disorder in which your child’s thyroid gland does not produce enough thyroid hormone. A child with an underactive thyroid may experience fatigue, weight gain, constipation, decreased growth, and a host of other issues.

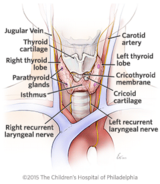

Your child’s thyroid is a small, butterfly-shaped gland in the front of the neck, just below the thyroid cartilage (Adam’s apple). Hormones produced by the thyroid affect all aspects of your child’s health including heart rate, energy metabolism (how effectively the body uses calories), growth and development.

Hypothyroidism is treatable with medication.

Types of hypothyroidism in children

There are several different types of hypothyroidism, including:

Congenital hypothyroidism

Congenital hypothyroidism (CH) occurs when the thyroid gland does not develop or function normally prior to birth. It is a very common problem, affecting about 1 in every 2,500 to 3,000 babies. In the United States, all states test for CH as part of their routine newborn screening process.

Many factors, including your family history, your child’s physical exam, the degree of hypothyroidism in your baby at the time of diagnosis, and the course of treatment over the first two to three years of life, will help your child's physician determine if the cause is hereditary (runs in your family), and if life-long therapy is required.

Autoimmune hypothyroidism: chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis

Acquired hypothyroidism is most frequently caused by an autoimmune disorder called chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis (CLT). In this disorder your child’s immune system attacks the thyroid gland, leading to damage and decreased function. The disorder was originally described by Japanese physician Hakaru Hashimoto and thus is often referred to by his name: Hashimoto’s thyroiditis.

CLT is more common in girls than in boys, and in adolescents more than pre-adolescents. Patients with other forms of autoimmune disease, most commonly insulin-dependent diabetes, are at increased risk of developing CLT. Overall, about 20 to 30 percent of diabetics will develop CLT. Because of this, annual screening for CLT is a routine part of diabetic care.

Iatrogenic hypothyroidism

Iatrogenic hypothyroidism is a form of acquired hypothyroidism that occurs in children who have had their thyroid gland medically ablated (destroyed) or surgically removed. By removing the thyroid gland, the body no longer produces thyroid hormone, leading to iatrogenic hypothyroidism.

Central hypothyroidism

Central hypothyroidism occurs when the brain does not make thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), the signal that tells the thyroid gland to work. This condition is much less common than disorders associated with an abnormal thyroid gland. In fact, in central hypothyroidism, most patients have a normal thyroid.

In addition to a low TSH, central hypothyroidism may be associated with deficiencies of other hormones, including:

- Growth hormone

- Adrenocorticotropic hormone, which stimulates the adrenal gland during stress

- Luteinizing and follicle-stimulating hormone, which control ovary and testicular function

- Prolactin, which helps females produce milk

- Oxytocin, which is important for childbirth and lactation

- Antidiuretic hormone, which controls urine production

Central hypothyroidism may occur due to abnormal development of the hypothalamus or pituitary glands (the location in the brain where TSH is made), trauma, a tumor or treatment for a tumor (i.e. surgery, radiation). Central hypothyroidism may be inherited, and boys and girls are affected equally.

Signs and symptoms of hypothyroidism

Symptoms of hypothyroidism are usually subtle and gradual, and may resemble those of other conditions or medical problems. Many symptoms are non-specific and may be ignored as normal parts of our everyday lives. Because of this, the condition may go undetected for years.

Symptoms may include:

- Fatigue and/or exercise intolerance

- Slower reaction time (an important issue for drivers)

- Weight gain

- Constipation

- Sparse, coarse and dry hair

- Coarse, dry and thickened skin

- Slow pulse

- Cold intolerance

- Muscle cramps

- Sides of eyebrows thin or fall out

- Dull facial expression

- Hoarse voice

- Slow speech

- Droopy eyelids

- Puffy and swollen face

- Enlarged thyroid, producing a goiter-like growth on the neck

- Increased menstrual flow and cramping in girls and young women

If you have concerns about your child's health, talk to your child’s physician.

Causes of hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism can be congenital (meaning your child was born with it) or acquired as your child grows. Genetics do play a role and some children — although not all — inherit the disorder from their parents. In some cases, the cause of hypothyroidism is unknown.

Depending on the cause of your child’s hypothyroidism, your child may be diagnosed with a specific type of hypothyroidism, which can affect treatment and long-term outcomes for your child.

Hypothyroidism and obesity

Severe hypothyroidism can lead to decreased metabolism and decreased use of calories. However, hypothyroidism is very rarely the cause of being overweight or obese.

Despite this reality, medical providers often order thyroid function tests as part of the routine screening in overweight patients. This is a reasonable practice. In addition, thyroid function testing should also be ordered at the same time as testing for elevated cholesterol, as hypothyroidism is associated with elevated LDL levels (“bad” cholesterol) due to decreased metabolism of LDL.

Being overweight is associated with mild elevations in thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) that are not a reflection of thyroid disease, but an association with excess weight. In other words, it is more common for excess weight to lead to a mild increase in TSH rather than a mild increase in TSH to result in a significant increase in weight.

In order to confirm the relationship between excess weight and a mild increase in TSH, your child's doctor should review the linear growth (gain in height) to determine if the increase in weight is accompanied by normal or increased height, as opposed to decreased linear growth, which is more frequently associated with hypothyroidism.

Your child’s doctor may also order laboratory testing for Hashimoto’s thyroiditis or elevated LDL and total cholesterol to determine whether the hypothyroidism should be treated.

Hypothyroidism and pregnancy

During the first few months of pregnancy, the fetus relies on the mother for thyroid hormone. Thyroid hormone plays an essential part in normal brain development. Maternal hypothyroidism can cause irreversible harm to the fetus. Early studies found that children born to mothers with hypothyroidism during pregnancy had lower IQ and impaired psychomotor (mental and motor) development. If properly controlled, often by increasing the amount of thyroid hormone, women with hypothyroidism can have healthy, unaffected babies.

Current recommendations include asking all women at the initial prenatal visit if they have any history of thyroid dysfunction or thyroid hormone medication. Laboratory screening of thyroid functions and/or thyroid antibodies should be considered for women at high risk of hypothyroidism. Detection and treatment of maternal hypothyroidism early in pregnancy may prevent the harmful effects of maternal hypothyroidism on the fetus. For women on thyroid hormone prior to conception, thyroid function testing should be performed regularly throughout pregnancy as it is very likely that the thyroid hormone dose will need to be increased. Women are encouraged to ask their primary care providers for further information and clarification on this important topic.

Testing and diagnosis

Diagnostic evaluation begins with a thorough medical history and physical examination of your child. The most common cause of congenital hypothyroidism is that the thyroid gland did not move to the correct location in the lower third of the neck during prenatal development.

At The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, clinical experts use a variety of diagnostic tests to diagnose hypothyroidism, including:

- Thyroid function screening, a blood test that measures thyroid hormone (thyroxine or T4) and serum TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone) levels. Hypothyroidism is diagnosed when the TSH levels are above normal and T4 levels are below normal. A less severe or earlier form of hypothyroidism is reflected by an elevated TSH and a low-normal T4, a condition called "compensated" or "subclinical" hypothyroidism.

- Anti-thyroid antibody level studies. Anti-thyroperoxidase (anti-TPO) and anti-thyroglobulin (TgAb) are elevated in autoimmune hypothyroidism. In contrast to the antibody found in Graves' disease (a type of hyperthyroidism), these have no function. They only serve as a indicator of the diagnosis.

- Thyroid ultrasound, which uses ultrasonic waves to image your child's thyroid and lymph nodes. An ultrasound does not expose your child to radiation. In some forms of hypothyroidism, the thyroid tissue will have an irregular appearance and there may be areas that look like a thyroid nodule. Expert review of the images by an experienced pediatric endocrinologist will determine if the area warrants further investigation with fine needle aspiration (FNA) or if it can be followed with repeat thyroid ultrasound to determine if FNA is needed. Ultrasound can also be used to ensure a newborn with congenital hypothyroidism has a normal thyroid in the correct location.

- Nuclear medicine uptake and scan, which helps determine how well your child’s thyroid tissue absorbs iodine, a key ingredient in making thyroid hormone. For the test, your child is give a very small amount of radioactive iodine — usually technetium 99m (TC-99m) or I-123 — then we measure how much iodine is absorbed (uptake) and the pattern of distribution of the radioiodine in the thyroid tissue (scan). This test can also be used to determine the location of thyroid tissue for newborns with congenital hypothyroidism.

Who should be screened for hypothyroidism?

- All children who fail the thyroid portion of their newborn screening

- All children with poor linear growth (height to weight ratio)

- All children who have had cranial irradiation as part of medical treatment for cancer

- All children with a history of severe brain injury or abnormal development

- Anyone with symptoms of hypothyroidism

- All pregnant women with a family history or symptoms of thyroid disease

Treatment for hypothyroidism

At The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, experts at the Pediatric Thyroid Center take a team approach to treatment for children with hypothyroidism. Our board-certified endocrinologists, pediatric surgeons and nurses collaborate to provide your child with individualized care and the best possible outcome.

Our Center is led by Andrew J. Bauer, MD, FAAP, a world-renowned endocrinologist and researcher, who is often sought for second opinions on difficult-to-diagnose thyroid disorders.

In most cases, hypothyroidism can be treated with thyroid hormone replacement pills (levothyroxine). Levothyroxine is chemically identical to thyroxine (T4), which occurs naturally in our bodies, and replenishes your child’s thyroid hormone levels to normal as long as it is taken as prescribed. The pills can be given to patients of all ages, from newborn to adult.

Uncommonly, patients may benefit from using both levothyroxine (T4) and liothyronine (T3). This option will be evaluated and discussed with you depending on your child's response to T4-only therapy, as well as your child's follow-up thyroid hormone laboratory values.

If your baby has hypothyroidism and medication is prescribed, you can crush the tablet and give it to your baby with breast milk, formula or water. Currently, there is no liquid form of the medication in the United States that is effective.

Older children can swallow or chew the medicine. Food can decrease the absorption, but in general, it is more important to remember to take the pill at about the same time every day (morning or night) than to be overly concerned about taking it on an empty stomach.

You should avoid giving the thyroid replacement pill to your child at the same time they are ingesting iron or calcium.

Your Child’s Appointment with the Pediatric Thyroid Center

Learn about what to expect during and how to prepare for your child's appointment with the Pediatric Thyroid Center at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

Outcomes for hypothyroidism

The majority of children with hypothyroidism — who are compliant with their medication — can achieve normal growth and development. Thyroid hormone replacement is weight- and age-based, so more frequent checks are needed while your child is still physically growing.

Resources to help

Hypothyroidism in Children Resources

Pediatric Thyroid Center Resources

We have created resources, including videos, to help you find answers to your questions and feel confident with the care you are providing your child.

Reviewed by Andrew J. Bauer, MD