What is sepsis?

Sepsis is an overwhelming and life-threatening response to infection that causes organ failure. Normally, when we get an infection, like a cold, sore throat, or stomach bug, our body’s immune system is able to fight off the bacteria or virus in a few days. Sometimes, infections can settle into more invasive parts of our body, like the lungs, causing pneumonia, or the kidney or bladder, causing a urinary tract infection, or even our bloodstream. These infections can make us sicker, and we often need antibiotics to help our immune system fight off the infection.

In sepsis, the combination of the body’s immune system and the infection together cause too much inflammation. This inflammatory response can prevent our organ systems, such as the heart, lungs, brain, liver, and kidneys, from working normally even if the infection is in a different part of the body. The most severe form of sepsis is called septic shock, which happens when the body’s inflammatory response affects our heart and blood vessels, causing blood pressure to fall below normal, which then further hurts our other organ systems.

Causes of sepsis

Sepsis occurs when the body develops an overwhelming response to an infection. Sepsis can be triggered by different kinds of germs, including bacteria (like E. coli), viruses (like influenza or “the flu”), and fungi (like candida), but is most often triggered when bacteria get into our blood, lungs, kidneys, or abdomen.

Bacteria live all around our environment, on our bodies, and even in our bodies (such as in our mouth and intestines). When bacteria get through our normal barriers, like a cut in the skin, sometimes our body’s immune system triggers an excessive inflammatory response as it tries to control the infection. As sepsis progresses over hours to days, it can cause problems with our heart, brain, liver and kidneys, and, in extreme cases, can lead to organ failure and death.

Children with sepsis are often critically ill, usually requiring emergency treatment and admission to a pediatric or neonatal intensive care unit (ICU). The exact reasons why some infections progress to sepsis is an area of active research.

Symptoms of sepsis

Sepsis usually begins as a serious infection, but can progress to an emergency quickly (sometimes over hours). Although most symptoms are not specific for sepsis, there are several warning signs that may signal the presence of sepsis:

- High body temperature (fever above 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit) or low body temperature (below 96.5 degrees Fahrenheit )

- High heart rate, even when fever comes down

- Breathing fast or trouble breathing

- Dizziness with standing up

- Significant fatigue, sleepiness or lethargy

- Confusion or agitation

- Rash, particularly bright red and warm areas or small reddish-purplish bumps that do not blanch or disappear when you push on them

- Less urine output than normal

Diagnosing sepsis

Unfortunately, there is no single diagnostic test to determine if somebody has sepsis. Usually, your doctor will measure your vital signs (temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and oxygen level) along with blood tests to look for signs of inflammation and problems with your organ systems. Additional tests to identify the source of infection, such as a blood culture, chest X-ray, urine test or CAT scan, may also be done.

Treatment for sepsis

Early treatment for sepsis, ideally started within the first hour after presentation to the hospital, improves outcomes. If your doctor suspects sepsis, fluids and antibiotics are typically given through an IV, and oxygen is often administered through a cannula or mask. Some children with sepsis need a lot of IV fluids and a few will require additional medicines to raise low blood pressure.

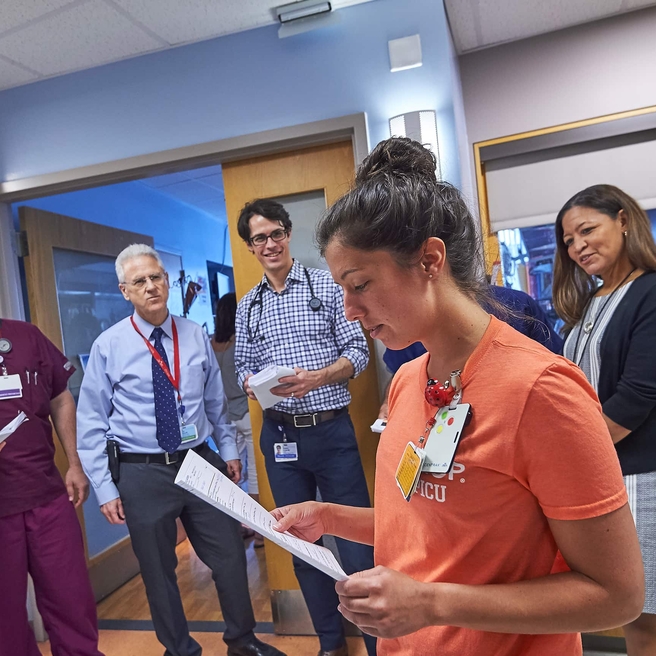

Depending on the severity of sepsis and the site of the infection, some children will require a temporary breathing tube and help of a ventilator to support their breathing while they are sick. Unless children improve quickly in the first few hours, ongoing treatment is best provided in a pediatric or neonatal intensive care unit, where doctors, nurses and respiratory therapists with special training in critical conditions like sepsis can monitor for improvement or worsening and adjust treatment accordingly.

When antibiotics alone are not expected to be enough to treat an infection, drainage of pus or even surgery is sometimes required.

Long-term outlook for children with sepsis

In the mid-1900s, over 90 percent of patients who developed sepsis died. With the development of targeted antibiotics and better emergency care, including intravenous fluids, medications to increase blood pressure, and supplemental oxygen, most patients who develop sepsis now survive. However, nationally, about 1 in 10 children with severe sepsis or septic shock are still at risk of dying. In addition, many survivors go on to have long-term problems with attention, managing emotions, school work, and physical activity, as well as a higher risk of recurrent infections and hospital readmission.

At Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), clinicians and nurses within the Pediatric Sepsis Program have established a Sepsis Survivorship Program to screen patients for potential long-term problems related to sepsis and support families in seeking help when needed.

Follow-up care for children with sepsis

After children are discharged from the hospital, they should follow up with their pediatrician and any other recommended specialists. Some children may require new physical therapy and/or occupational rehabilitation for a period of time. Most children recover back to their baseline by a few weeks to months after sepsis, but some children have lingering issues with attention, emotions, school work, or physical activity. If your child does not seem to be him or herself within one or two months after treatment for sepsis, you should contact your pediatrician or another trusted health professional or contact the CHOP Pediatric Sepsis Program.

Why choose us?

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia is an international leader in clinical care, quality improvement, education and research related to childhood sepsis. Physicians, nurses and other healthcare professionals in the Emergency Department, intensive care units and other specialties have substantial expertise in recognizing and treating infants and children with sepsis and septic shock, with over 200 cases of childhood sepsis treated per year at CHOP.

In addition, the CHOP Pediatric Sepsis Program is a group of multi-professional specialists who work throughout the hospital to ensure the highest quality care for children with sepsis and to state-of-the art therapies when necessary, including antimicrobial stewardship, advanced modes of ventilation, dialysis, plasmapheresis and ECMO.

Resources to help

Pediatric Sepsis Program Resources

Caring for a child with any illness or injury can be overwhelming. We have gathered resources to help you find answers to your questions and feel confident with the care you are providing your child.