Breakthroughs. Every day.

Find care you can count on

Whether it’s a quick trip to urgent care or a specialist visit for a complex condition, we’re here for your family, when and where you need us. Discover our full spectrum of expert care, for everything from the routine to the rare.

Explore care options

Best in nation year after year

We're thrilled to once again be named one of the Best Children’s Hospitals in the nation by U.S. News & World Report! From clinical expertise to life-changing research, we offer best-in-nation pediatric care for everything from the routine to the rare.

Driven to discovery

At Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, we are charting the unknown. Fueled by an endless curiosity, we translate groundbreaking research into life-changing solutions for every child we serve.

The Future of Personalized Medicine is Here: KJ’s Story

KJ received a first-of-its-kind personalized gene editing therapy at CHOP to treat his urea cycle disorder.

Caring for your child at every age

At every age, and every stage, we’re here for your child – and for you. Learn from our leading experts how to support your child’s health, from birth through young adulthood.

Empowering community health, together

We know improving child health means addressing the challenges families face outside the walls of our hospital. Learn how we’re partnering with community and government leaders to create healthier futures for children across our region.

World's First Patient Treated with Personalized CRISPR Gene Editing Therapy at CHOP

Landmark study from CHOP and Penn Medicine showcases the power of customized gene editing therapy to treat patient with rare metabolic disease.

CHOP Receives Largest Single Gift in its History to Create Roberts Children’s Health

Transformational $125 million gift will support a new state-of-the-art hospital set to shape the future of pediatric care.

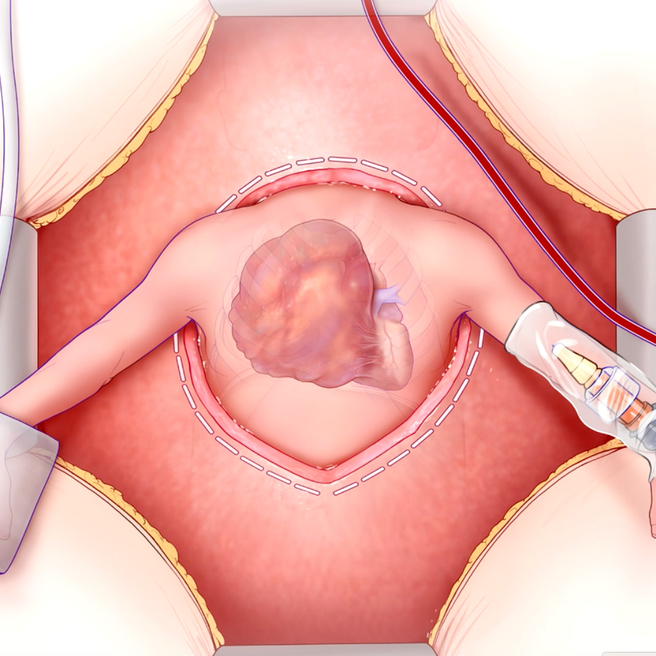

A Lifesaving Fetal Heart Surgery

CHOP’s Center for Fetal Diagnosis and Treatment and Fetal Heart Program, successfully remove rare tumor from baby’s heart while still in the womb.

Join us and give back

Imagine a future where all children have a chance to grow and thrive. You can help make it happen. There are many ways to support CHOP, and every gift makes a difference.