Breakthrough Treatment for Airway Tumors Gives Hannah Her Voice

Breakthrough Treatment for Airway Tumors Gives Hannah Her Voice

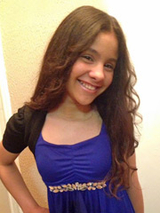

For most of her 15 years, Hannah Leon couldn’t talk, only whisper, because she had a severe form of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (RRP), a condition that results in benign tumors that grew on her vocal cords and airway.

But now she can talk with her friends — really talk — because all the tumors are gone, thanks to an experimental treatment she received at the Center for Pediatric Airway Disorders at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP).

It’s one outcome her doctor, otolaryngologist Karen Zur, MD, declared was “really, really cool.” She’s treated Hannah since she was 3, and for most of those years, Zur was frustrated she wasn’t able to do more.

Relentless papilloma growth

Hannah’s RRP was so aggressive that the small, wart-like tumors (known as papillomas) grew rapidly and kept blocking her airway. At 1½, she had a tracheostomy, a hole cut into her throat to open up an avenue for air to get to her lungs to bypass the areas of blockage. The tracheostomy tube and the tumors also inhibited her speech, just as the toddler was finding her voice.

“When she was 2, a speech therapist gave her adaptive equipment, a computer with a touch screen to create words,” Hannah’s mother, Glamiris Cabrera, remembers. “She didn’t like it and wouldn’t use it. She would whisper instead. I’m a woman of faith. I felt then she was going to speak one day. And here we are, 13 years later.”

Those years in between were difficult. Zur needed to surgically remove the tumors in Hannah’s trachea (windpipe) and on her vocal cords frequently. As Hannah got older, she needed the “debridement” procedure every week or two. Hannah and Cabrera would make the 2½-hour drive from Edgewater, NJ, to CHOP for the surgery, which required general anesthesia.

Still, Hannah’s RRP was relentless.

Most medications ineffective against RRP

To make things smoother once Hannah started school, Cabrera would come to her classroom during one of the first days of the year to talk to the class.

“I would explain what was going on with the trach and show them the portable suction machine and oxygen meter,” she says. “Hannah would tell them from the very beginning: ‘No touch! That’s how I breathe.’ She’s always been outgoing. Despite missing a lot of school days sometimes a month at a time — with being sick and doctor’s appointments — she kept up.”

Lung infections were common. Zur tried every trick in the RRP book to lessen the effect of the disease.

“Over the years, we had tried a variety of medications,” Cabrera says. “Everything was off-label, experimental for RRP, but I was willing to try it if Dr. Zur said it might help. Unfortunately, nothing really helped stop the papillomas in her trachea.”

Hannah did get some relief for the tumors in her lungs by taking injections of interferon, a medication used to treat various cancers, beginning when she was 5 years old. The papillomas in her throat and windpipe kept growing back. She also had lung abscesses that twice landed her at CHOP for extended inpatient stays.

Finally, a breakthrough with a German assist

A couple of years ago, Zur read a journal article about a hematologist at the University Hospital Muenster in Germany, Michael Mohr, MD, who tried infusions of the cancer drug bevacizumab on five patients with advanced, progressive RRP. All five showed an immediate response to bevacizumab treatment.

“Sometimes it’s a happy accident, someone thinking outside the box when it comes to finding a treatment that works,” Zur says. She shared the information with Cabrera and Hannah, then 12, who were enthusiastic to try it. CHOP granted a “compassion exception” to use bevacizumab (brand name Avastin®) for Hannah since it was an off-label use. Avastin, which appears to inhibit the growth of new blood vessels that can feed tumors, had been used in pediatric cancer patients for several years.

“We saw improvement right away,” Cabrera says. “I’m very familiar with the pictures of Hannah’s vocal cords since we’ve had so many laryngoscopies. The papillomas looked like little pieces of cauliflower. When I saw the images after her Avastin treatment, I gasped.”

No more tumors

After Hannah’s second Avastin infusion, her vocal cords and most of the trachea were clear of papillomas. “It was jaw-dropping when I saw her for a follow-up visit,” Zur says. “I was able to remove her tracheostomy tube. She didn’t need it anymore.” The remaining tracheal lesions and the lung lesions resolved as well with several more infusions of this drug.

Hannah has maintenance Avastin treatments every two months now, under the supervision of oncologist Elizabeth Fox, MD, and has experienced no side effects. She now returns to the operating room twice a year to confirm that the tracheal disease is no longer present.

“This has the potential to revolutionize the conversation on RRP,” Zur says. “The frontline treatment has always been to surgically remove the papillomas. But surgery always carries the risk of scarring in the vocal cords, and we can’t fix scars. If we can prevent the tumors from growing, and surgery is not needed, we could also prevent permanent voice issues. Papillomas can become cancerous. Also, anytime you have anesthesia, there’s always a risk."

“We’re beginning to think: Should we change the paradigm and make Avastin the primary treatment?”

CHOP: Setting the standard

Since Hannah, Zur has successfully treated two additional children with RRP with Avastin, and a fourth patient ready to go once he obtains insurance approval. That makes CHOP the most experienced center in the United States providing this groundbreaking therapy.

CHOP is leading a nationwide study that tracks doses of Avastin and patient outcomes as a way to determine which protocols work best. It’s a slow process because, luckily, RRP is a rare condition, with estimated occurrence of 2 in 100,000 kids in the United States. Children experience varying degrees of severity. Some have tumors only on their vocal cords; for others, like Hannah, the entire airway in involved.

RRP occurs when a baby is born to a mother with active human papillomavirus (HPV). But, considering about one-quarter of the U.S. population has HPV, only a small percentage of babies born to mothers with HPV contract RRP, and scientists have not been able to figure out why that is.

Zur is optimistic that incidences of RRP will fade away as a generation of women of child-bearing age never contract HPV because boys and girls received HPV vaccinations in their teens. For example, in Australia, where HPV vaccinations are provided free in schools (since 2007 for girls and since 2013 for boys), the HPV rate among women 18 to 24 years of age dropped from 22.7 percent in 2005 to 1.1 percent 2015. “That is my hope for the United States,” she says.

A typical teen with a future in mind

Three years after receiving Avastin for the first time, Hannah continues to be tumor-free. During a recent appointment for maintenance therapy, she proved to be the epitome of a typical teen — albeit one who’s more medically savvy than most.

“I like dancing and hanging out with my friends,” she says, her voice a little hoarse but clear and strong. “We go shopping or out to eat or we stay at someone’s house and listen to music or watch movies. My friends have always been really supportive.”

She can do pretty much whatever she wants to now. Volleyball is good. Playing soccer, she needs to take breaks since she has diminished lung function due to the abscesses and residual scarring from so many papillomas over the years.

One big difference? On her family’s annual lake vacation, she is finally able to go under the water because the opening in her neck where the tracheostomy tube used to be is closed.

Hannah has many positive memories of the long hours and days she’s spent at CHOP. Nurses in the post-surgery area were always sure to have her favorite snack, Cheerios® and milk, waiting when she awoke. “I remember being very excited to do the arts and crafts. It was fun,” she recalls. Those times have also influenced her future.

“I’ve been saying for a long time that I want to be a nurse,” she says. “I do love kids, so probably a pediatric nurse.”