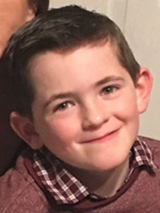

Genetic Testing for Epilepsy Helped Ryan Be the Rambunctious Kid He Is Today

Genetic Testing for Epilepsy Helped Ryan Be the Rambunctious Kid He Is Today

Jennifer and Derek were excited to celebrate their 5-month-old son, Ryan’s, first Christmas. But on Christmas Eve, Ryan experienced a frightening episode: He went stiff as a board in his mother’s arms, stopped breathing, and turned blue.

“Petrified,” is how Jennifer describes how she felt.

The episode lasted less than a minute. By the time an ambulance arrived to the family’s house in Drexel Hill, PA, Ryan was back to normal. He was taken to Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), where physicians performed a basic neurological workup, but all the tests came back normal, so he was discharged home after 12 hours.

Life went back to normal for the family until three weeks later, when a similar incident happened again. Ryan was rushed back to CHOP. This time, he was diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux. He was prescribed anti-reflux medication, but when he suffered another episode two days later, CHOP pediatric neurologists Ethan Goldberg, MD, PhD, and Ingo Helbig, MD, suspected something else was going on.

Ryan was admitted to the hospital and underwent a week of continuous video electroencephalogram (EEG) testing, which confirmed the episodes weren’t reflux; they were seizures.

The cause of the seizures couldn’t be identified, so it was difficult to determine the most effective way to control them. Ryan’s care team spent months trying different types of medication in various combinations and at different doses to manage his seizures.

Seizures return

A relatively stable period came to an end on the day of Ryan’s fourth birthday party, when Jennifer noticed a rash on his legs. A rash for someone on anti-seizure medication can indicate an unpredictable but potentially deadly allergic reaction. Jennifer took a picture of Ryan’s rash and texted it to Dr. Goldberg, who requested the family come in for an evaluation first thing the next day. He instructed Jennifer not to give Ryan another dose of the medication.

The next morning, as Jennifer was getting Ryan ready for the appointment, he had a seizure. This time, when the medics arrived, Ryan was still seizing. He continued to have one seizure after another, without ever regaining consciousness. He was rushed to CHOP, admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), and placed in a medically induced coma, which finally stopped the seizures.

When Ryan’s physicians initially tried to bring him out of the coma, he didn’t wake up. Eventually, after several days, Ryan started to wake up on his own. It was only then that the true impact of the continuous seizures became clear. Ryan had lost the ability to walk, talk, eat, drink and even play.

“It was like I brought a 4-year-old to the hospital and he became an infant again,” says Jennifer. “That was almost worse than the seizures because we didn’t know if he was going to be like that forever.”

The seizures also damaged the nerves in his eyes, rendering him temporarily blind. Ryan spent the next three months in the hospital recovering. His rehabilitation was slow, but over time, with the help of speech therapy, language therapy, occupational therapy and physical therapy, he started to make progress. His vision returned to 20/20.

Donations Power Discoveries

Your gift fuels research that could change the lives of thousands of children like Ryan who live with epilepsy.

Providing answers for unexplained epilepsy

Thankfully, in the time between Ryan’s initial diagnosis and his return to the hospital, researchers at CHOP and around the world made significant headway in understanding the genetic causes of epilepsy, which included rapid advancements in clinically available genetic testing. Identifying a genetic cause of epilepsy is a critical first step in understanding the specific seizure disorder and can lead to more personalized care.

During Ryan’s hospital stay, the epilepsy neurogenetics team at CHOP drew blood for genetic testing, which was not available when Ryan was first diagnosed with epilepsy several years earlier. Results from the testing revealed he had a very rare genetic epilepsy triggered by a disease-causing variant in the gene SCN8A.

Since Ryan’s genetic diagnosis was made, CHOP has established the Epilepsy Neurogenetics Initiative (ENGIN), a specialized program that strives to diagnose, treat, and ultimately cure epilepsy through genetic testing, neurophysiologic testing, and individualized therapy. ENGIN works hand in hand with the Pediatric Epilepsy Program to make a genetic evaluation available to all children with epilepsy, which may have meaningful implications for medical management or treatment. Now, genetic testing is part of the initial workup of epilepsy for children like Ryan.

For genetic epilepsy, knowledge is power

Knowing the genetic source of Ryan’s epilepsy has been a huge benefit to Ryan and his family. This diagnosis enabled Dr. Goldberg to prescribe a specific combination of anti-seizure medications known to control it.

It provided other important information about Ryan’s condition: That it is lifelong and associated with intellectual delays, disability and autism. It made the family aware that the genetic variant that causes Ryan’s epilepsy may affect his heart, so he’s now followed by a CHOP cardiologist. The testing also showed that, while genetic, this mutation is not inherited; rather, it is new in Ryan and did not come directly from his parents. This told his parents that the recurrence risk for a future brother or sister is extremely low.

It takes three medications, but Ryan is now enjoying life nearly seizure free. He’s a rambunctious, strong-willed and resilient 8-year-old who loves to play outside.

“I wholeheartedly believe either Ryan would not be here at all today or would not be doing as well as he is if it were not for the genetic testing of Dr. Goldberg and CHOP,” says Jennifer.

“If you were to look at him, you wouldn’t know anything is wrong,” she continues, thinking back on the prolonged seizures that he once suffered. Ryan does require special education support, but he’s in a mainstream classroom and continues to make consistent developmental progress.

“The fact that he’s doing so well is a miracle,” says Jennifer. “He’s been through so much. We never expected him to be where he is today.”