Leigh Syndrome: A Family’s Quest for Answers

Leigh Syndrome: A Family’s Quest for Answers

Nearly four decades after Marsha and Allen Barnett lost two of their three sons to a puzzling and deadly childhood disease, researchers at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) could finally answer the question: What killed Chuckie and Michael Barnett?

The brothers — aged 5 and 10 when they passed away — died two years apart in the early 1980s after a series of debilitating symptoms attacked their nervous systems and sapped their energy. After the deaths, doctors were only able to provide a name for the disease — Leigh syndrome. The exact gene mutation that caused the brothers’ syndrome remained a mystery for more than 35 years.

In 2018, CHOP researchers identified the Barnett family’s specific inherited mutation: a change in one nuclear gene that arose spontaneously in previous generations of both parents’ Ashkenazi Jewish ancestors. The revelation prompted the Barnetts to offer additional support for mitochondrial research at CHOP that could help other families facing complex or unknown mitochondrial disorders.

The Barnetts pledged $2 million to CHOP to establish the Barnett Family Mitochondrial Medicine Research Endowment. The fund will advance mitochondrial research and support the ongoing work of Marni J. Falk, MD, Executive Director of Mitochondrial Medicine, and Douglas C. Wallace, PhD, Director of the Center for Mitochondrial and Epigenomic Medicine. These clinical and research programs work closely together to find answers, improve care and develop precision therapies for mitochondrial disease patients of all ages.

“The Barnett family waited more than three decades for answers about the genetic cause of the disease that took their two oldest sons,” Dr. Falk says. “Because of advances in genetic technologies, many families can now be given a definitive mitochondrial diagnosis in months, or sometimes, even weeks.

“The Barnett family’s generous funding support will enable us to find answers for more families, which is essential to guide our ability to develop and offer advanced care and treatments.”

Dr. Falk adds, “the ultimate impact of their support is to improve the quality and quantity of life for children and adults affected by the diverse array of mitochondrial diseases."

Chuckie and Michael

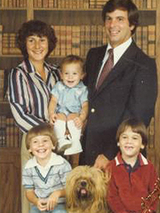

Raising three boys in the late 1970s was hectic, but Marsha and Allen wouldn’t have had it any other way. Their oldest, Michael, was unusually bright. He started reading at age 3 and enjoyed talking with the adults in his life. Their middle child, Chuckie, was a happy and easy-going child who didn’t let small motor challenges — like struggling to use scissors in nursery school — get him down. Their youngest, Jeffrey was a natural athlete who was always sensitive to other people. Even at 2½ years old, Jeffrey ran faster than his older brothers, but seemed to gauge their abilities and adjust.

Chuckie was the first to exhibit troubling symptoms — repeated low-grade fevers, a staggering gait, unusual weight gain, labored breathing, and eventually, loss of muscle control of his eye movements. The Barnetts repeatedly brought him to doctors and hospitals, yet no one could explain the cause or meaning of his unusual symptoms.

When the family took a road trip to visit friends in Massachusetts, Chuckie fell ill again. This time, his symptoms were more extreme: his heart raced; his lungs filled with fluid. His parents rushed him to the hospital, where doctors and nurses failed in their attempts to resuscitate him. In what seemed like a moment, Chuckie had died.

In shock, parents Marsha and Allen had a million questions and no answers. Even as they buried Chuckie, they worried about what the future held for Michael, who had experienced some of the same troubling symptoms Chuckie exhibited before his death.

An autopsy revealed Chuckie died of Leigh syndrome, a rare, inherited disorder that involves metabolic strokes deep in the brain and is now recognized to result from impaired cellular energy production. Patients with Leigh syndrome may also develop progressive weakening of the muscles, heart and central nervous system.

At the time however, doctors could not specify what potential gene disorder had caused Chuckie’s disorder, even as Marsha and Allen desperately hoped Michael would not share the same fate.

“I think we knew what was going to happen to Michael, but we still hoped: for a new treatment, a new test, something that could prevent an ending like Chuckie’s,” Marsha says. “When doctors told us that we’d have the same outcome with Michael, we were crushed.”

Marsha remembers Michael’s 10th birthday like it was yesterday. The family was at the circus with friends when a quizzical look crossed Michael’s face and he covered one eye. When Marsha asked him what was wrong, he said he was seeing double. Marsha felt her stomach drop: eye disturbances were one of the final symptoms before Chuckie’s death. Two months later, Michael also died.

Marsha and Allen

Losing their oldest boys forever changed the lives of Marsha and Allen Barnett and Jeffrey, their youngest and sole surviving son. When they learned Michael would share Chuckie’s fate, the family pulled inward. But Michael’s death pushed them to open up and share their story, to talk about their beloved sons and to search for “a new normal” for their family. Talking was both cathartic and motivating. It made them look for positive ways to honor their sons and help other families.

The family raised funds for mitochondrial research at the local, non-profit hospital that had treated their boys. When the hospital privatized in the 1990s, the Barnetts transferred their philanthropic support to Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and began to build relationships with both hospital and clinical leaders.

The couple met with then-CEO Steven M. Altschuler, MD; and some of the hospital’s earliest researchers in mitochondrial medicine. Dr. Altschuler encouraged the Barnett family to increase their financial support to include an endowed chair in mitochondrial medicine.

More about mitochondrial disease

Mitochondrial disease occurs when dysfunctional mitochondria fail to produce enough energy for cells to function, affecting organ function in any body system.

Years later, the family was invited to a meeting to discuss research progress and met a promising young researcher, Dr. Falk. The family was fascinated by her research and enjoyed visiting her lab and observing her work. When CHOP leaders told the Barnetts they were considering hiring Dr. Wallace, a mitochondrial pioneer the family had a previous relationship with, they were enthusiastic about the opportunity for him to come to CHOP as the Barnett endowed chair.

“This growing, world-leading program is an excellent example of CHOP under promising and over delivering,” says Allen Barnett.

Over the next two decades, the Barnetts remained connected to CHOP — thanks to Dr. Falk and Dr. Wallace — with phone calls, emails and visits. It was these relationships that proved to be key to the answers the Barnetts had long sought.

Jeffrey and Rachel

Throughout his childhood, Jeffrey was well aware his brothers had died, but he still considered them part of his family. At 6 years old, he frequently introduced himself to new friends by saying, “Hi. My name is Jeff. I have two brothers, but they died.” By third grade, he’d realized it was more socially acceptable to simply introduce himself as an only child.

Early genetic testing was limited, but available medical and genetic counseling knowledge at the time suggested Jeffrey was unlikely to suffer the same fate as his brothers. He grew and developed normally, was a gifted athlete and participated in many fundraising efforts with his parents over the years. “Looking back, there has been no more defining experience in my life than my brothers dying,” Jeffrey says. “My parents were so beat up by it.”

With no symptoms, Jeffrey moved on with his life, went to college, and met his future wife, Rachel. When the two married and considered having children, Marsha gave the young couple all the research she had amassed about Leigh syndrome and encouraged them to undertake genetic testing.

The young couple turned to Dr. Falk at CHOP for advanced genetic counseling to understand their risks of passing on the disease that had killed Jeffrey’s brothers. While they did not yet know the exact genetic cause of Leigh syndrome in Michael and Chuckie, the clinical genetics team within Mitochondrial Medicine at CHOP was able to reassure them that Jeffrey’s future children were unlikely to have Leigh syndrome.

While there are many genetic modes of inheritance for Leigh syndrome, if Jeffrey’s brothers had a mitochondrial DNA disorder, than Jeffrey (a male) could not pass it on. Other inheritance patterns for Leigh syndrome — autosomal dominant or X-linked — were possible, but unlikely given that Jeffrey was healthy. The most likely cause was an autosomal recessive condition, meaning that even if Jeffrey was an unaffected carrier of the gene mutation, it was extraordinarily unlikely his children would also inherit a mutation in the same causal gene from their mother that would be required for them to have a 25% chance of being affected.

The family was thankful for this clinical guidance, and based on this knowledge, Jeffrey and Rachel chose to begin their family. The couple’s two sons, Asher and Parker, now 11 and 6, show no signs of the disorder.

Unlocking the mystery

The young couple’s desire for answers prompted CHOP researchers and clinicians to take a fresh look at Chuckie and Michael’s DNA with a new lens. In the 30-plus years since the boys’ deaths, scientific knowledge about genetic, metabolic and mitochondrial disorders had expanded many-fold. Today, disease-causing mutations in nearly 100 different genes have been causally linked to Leigh syndrome.

In 2018, Dr. Falk called Marsha Barnett to ask about Chuckie’s and Michael’s specific symptoms. Dr. Falk was leading a research team that identified a candidate mutation in the gene USMG5 (now known as ATP5MD) in DNA from one of the Barnett brothers’ muscle tissue that had been frozen for three decades in Dr. Wallace’s research laboratory. This same mutation was simultaneously identified by Dr. Falk in another CHOP Leigh syndrome patient, and ultimately found in a fourth child as well.

The mutation was present on both copies of each child’s USMG5 gene, consistent with Dr. Falk’s suspicion that they had an autosomal recessive genetic disorder. This gene makes an essential protein in the ATP synthase enzyme that generates cellular energy. Its dysfunction could well have caused the rapid deterioration the Barnetts witnessed in their children.

After extensive further studies to validate the mitochondrial dysfunction caused by this mutation, the research team conclusively linked the newly-identified gene mutation to Leigh syndrome.

This major breakthrough provided an answer to the Barnetts’ mystery of nearly 40 years. Instead of simply being content to finally have a reason for their family’s struggle, the Barnetts looked at this identification as a milestone in their journey — one that was the perfect springboard to formalize the family’s ongoing philanthropic partnership with CHOP.

After discussion with the Mitochondrial Medicine team and CHOP’s Foundation, the family pledged $2 million to CHOP to establish the Barnett Family Mitochondrial Medicine Research Endowment. The permanent fund will advance mitochondrial disease research, support the work of Dr. Falk and Dr. Wallace, and forever link the Barnett family with mitochondrial medicine.

“The things that Doug (Wallace) and Marni (Falk) and CHOP do seem like quantifiable magic,” says Jeffrey Barnett, now 42. “Instead of merely saying thank you, my parents are fueling this research that will help the next generation of researchers to continue discovering more to help real families — like mine — find answers.”