Complexities of Treating the TSC Patient

Published on

Children's DoctorPublished on

Children's DoctorRead a case study from the Division of Neurology about an 8-year-old female with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) and the increased complexities of treating her symptoms.

An 8-year-old female with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) presents for a follow-up appointment with daily seizures despite treatment with two antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). At 7 months of age, she developed infantile spasms consisting of flexor extensor spasms with increased irritability and developmental regression. On examination she had hypomelanotic macules. An MRI of the brain showed classic features of TSC including cortical tubers and subependymal nodules. Her infantile spasms responded quickly to vigabatrin. At 18 months of age she developed partial seizures involving eye deviation to the right and right arm tonic clonic seizures. Unfortunately, despite treatment with multiple AEDs over 7 years, she continues to have 5 seizures per day that have her sent home from school frequently and hinder her from going to sleepovers. Her parents are concerned with her sleepiness related to her high dose of AEDs and her increasing seizure frequency; they want to discuss the next treatment options.

Discussion: Tuberous sclerosis is an inherited neurocutaneous disorder with abnormal growths in multiple organs including the brain, heart, lung, eye, and kidney. This abnormal growth results from a mutation in either the TSC1 or TSC2 gene, which code for hamartin and tuberin, proteins involved in a cascade that regulates cell growth. Genetic testing for TSC1 and TSC2 is available, but diagnosis is based on clinical manifestations of the disease. Based on the diagnostic criteria for tuberous sclerosis complex, a patient has TSC if he or she has 2 major features or 1 major feature with 2 minor features. A possible diagnosis is made if the patient has either 1 major feature, 1 major and 1 minor, or >2 minor features.

Adopted from Roach ES. J Child Neurology. 1998

The hypomelanotic macules are often present at birth and become more apparent as a child gets older. A Wood’s lamp aids in identifying these macules. Angiofibromas appear in preschool age and may progress into teenage years along the nasolabial folds as raised erythematous lesions. Shagreen patches also appear in teenagers as a flesh-colored raised lesion commonly seen on the lower flank and back. Ungual fibromas are flesh-colored lesions of the nail.

A formal ophthalmologic exam with a dilated fundoscopic examination is recommended for patients newly diagnosed with TSC to assess for retinal hamartomas, which are commonly asymptomatic but may cause visual impairment. Patients are also advised to have a renal ultrasound, which detects renal angiomyolipomas. Angiomyolipomas may cause increased blood pressure and kidney failure. There is a risk for angiomyolipomas to bleed and evolve into renal cell carcinoma. Cardiac rhabdomyomas may be detected on fetal ultrasounds or are first diagnosed by echo to evaluate a cardiac murmur. They may cause cardiac arrhythmias or obstruction of blood flow.

Cardiac rhabdomyomas shrink in size with time and thus cause fewer complications as a child gets older. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis presents in adolescent and young adult females presenting with shortness of breath, hemoptysis, and pneumothorax. Subependymal nodules are abnormal growths of the subependymal lining of the ventricles.

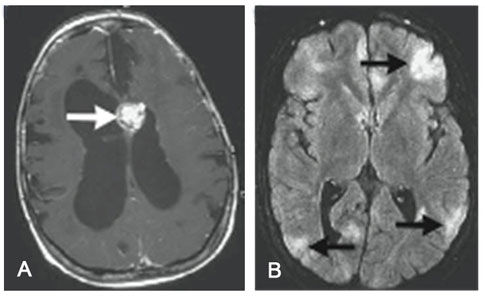

Subependymal nodules may grow into subependymal giant cell tumors (see Figure 2A). These nodules can cause obstruction of cerebral spinal fluid, especially at the foramen of Monro, resulting in increased intracranial pressure. Treatment includes surgical resection or everolimus, an immunosuppressant that inhibits the mTOR pathway. Tubers are cortical dysplasias that, unlike subependymal nodules, do not grow (see Figure 2B). However, the abnormal brain tissue around the tuber is epileptic. The total number of cortical tubers does not correlate with the severity of disease. For example, our patient has a small tuber burden but has medication-resistant epilepsy.

A: Subependymal giant cell tumor; B: Tubers

Crino P, et al. The tuberous sclerosis complex. NEJM. 2006;355(13):1345-1356.

Through the TSC Clinic at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, we offered our patient alternative treatments for her seizures including the ketogenic diet (KD) and epilepsy surgery. The TSC Clinic works closely with CHOP’s KD team of neurologists and nutritionists. The TSC Clinic collaborates with CHOP’s Pediatric Regional Epilepsy Program and neurosurgeons to assess if a patient is a surgical candidate. We also discuss new research assessing the efficacy of everolimus in treating seizures in TSC patients.

The TSC Clinic was devised to coordinate the multidisciplinary care provided by the cardiologists, nephrologists, neurogeneticists, dermatologists, developmental pediatricians, and social workers involved in caring for our TSC patients. We also strive to provide compassionate care and support to family members involved in the lives of their children with TSC.

Crino P, et al. The tuberous sclerosis complex. NEJM. 2006;355(13):1345-1356.

Krueger DA, et al. Everolimus long-term safety and efficacy in subependymal giant cell astrocytoma. Neurology. 2013;80(6):574- 580.

Roach ES, et al. Diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol. 2004;19(9):643-649.

To refer a patient to the Division of Neurology or one of its specialty programs, call 215-590-1719.

Contributed by: Katherine S. Taub, MD

Categories: Neurology, Children's Doctor Summer 2013