Case:

A 1-month-old male infant presented to the pediatrician’s office because of poor feeding and increased sleepiness. His point-of-care glucose was 42 mg/dL. He was referred to the closest hospital for evaluation.The infant had been born at 38 weeks of gestation by scheduled C-section. He was large for gestational age with a birth weight of 4310 g. The pregnancy was uncomplicated except for the finding of glucosuria on the mother later in the pregnancy (earlier testing for gestational diabetes was negative). His initial glucose was 19 mg/dL, he was fed 35 mL of formula and his repeat glucose was 40 mg/dL. However, because of persistent hypoglycemia and hypothermia he was transferred from the regular nursery to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). In the NICU he required intravenous dextrose (D17.5%) for 3 weeks. Off the fluids and on fortified breast milk (24 kcal/oz), his glucoses were mostly >60 mg/dL with some occasional glucoses

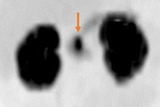

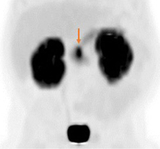

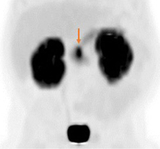

Upon subsequent admission at 1 month of age, the infant was diagnosed with hyperinsulinism (HI). He was unresponsive to treatment with diazoxide, the only Food and Drug Administration-approved drug for HI, and was transferred to the hyperinsulinism program at CHOP for further evaluation and management. He was found to be heterozygous for a recessive, paternally inherited, disease-causing mutation in ABCC8, one of the two genes encoding the beta cell ATP-sensitive potassium channels (KATP channels). This finding was predictive of focal hyperinsulinism. Specialized imaging with 18F-DOPA PET scan revealed a focal lesion located in the head of the pancreas. (See Figure 3). He underwent a 20% pancreatectomy to remove the lesion with complete resolution of the HI.

Discussion: Hyperinsulinism is the most common cause of persistent hypoglycemia in neonates, infants, and children. HI is caused by dysregulated insulin secretion from the pancreatic ß-cells and can be the result of perinatal factors (also known as perinatal stress-induced HI), part of a syndrome (such as Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome), or monogenic, due to genetic mutations. While the monogenic forms of HI are rare (1 in 50000 live births), HI due to perinatal stress is quite common and can affect up to 50% of at-risk neonates. Clinical presentation of infants with HI is characterized by severe and persistent hypoketotic hypoglycemia. The most common and severe genetic form of HI affects the KATP channels, which are the targets of diazoxide, rendering this drug ineffective and thus, infants with this form of HI more frequently require pancreatectomy to control the hypoglycemia. There are 2 distinct histological forms of HI: a diffuse form, in which all pancreatic ß-cells are affected; and a focal form, in which only a small area of the pancreas is affected. Focal HI, which accounts for approximately 50% of these cases, can be cured by surgical excision of the lesion.

The management of infants with severe HI can be very challenging and requires a consorted cooperation between multiple disciplines. Recognizing this need, CHOP founded the Congenital Hyperinsulinism Center in 1998, creating the first multidisciplinary team (see Table 1) dedicated to the care of children with HI.

The clinical expertise of the center is unique. Since its creation, the program has evaluated and treated >1300 children with HI and has operated on >525 children with severe HI.

Patients from all over the United States—and from 18 countries—have come to Philadelphia for treatment. Our specially trained transport team accompanies patients, maintains their glucose levels in transit, and safely delivers them for additional treatment. Because our NICU and endocrinology unit see so many HI patients, nurses are especially attuned to caring for these babies before and after surgery.

We have the largest single center experience using 18F-DOPA PET for the pre-surgery identification and localization of focal lesions, with more than 400 patients undergoing the procedure. Our approach has significantly impacted outcomes, with 97% of infants—more than 215 patients—with focal HI now cured after surgery.

The center’s translational research program aims to address the knowledge gap (underlying genetic cause is unknown in 50% of cases) and lack of effective medical treatments (only 1 FDA-approved drug). Ongoing investigations range from molecular studies in cells to clinical trials with novel therapies in affected patients. The center’s designation as a CHOP Frontier Program in 2019 means additional funds for research and expansion that seeks to further innovate by using personalized medicine to treat children with the condition. Goals include building a multidimensional patient data collection platform, developing more accurate diagnostic tools for insulinomas, and accelerate late-stage clinical trials for a promising CHOP-patented compound that ameliorates HI.

Unfortunately, despite all the advances of the last 25 years, children with HI continue to have long-term consequences because of hypoglycemia-induced brain damage. Up to 48% of these children have neurodevelopmental deficits, including speech delays, learning disabilities, and fine and gross motor delays, among others. These problems are preventable if diagnosis is made early and treatment is effective.

One key goal of the 2015 Pediatric Endocrine Society guidelines for evaluating and managing hypoglycemia in neonates, infants, and children is the prompt recognition and evaluation of infants with persistent hypoglycemia disorders.

According to these guidelines, the severity and persistence of the hypoglycemia in the case discussed at the beginning of this article should have prompted a thorough evaluation to determine its underlying cause and the demonstration that the infant could maintain normal plasma glucose concentrations (which after the third day of life should be >70 mg/dL) prior to discharge. Just as a child with fever would not be sent home without an investigation for the underlying cause of the fever, a child with hypoglycemia should not be discharged without a diagnosis, because just as with fever, hypoglycemia is a sign, not a diagnosis.

References and Selected Readings

- Lord K, De Leon DD. Hyperinsulinism in the neonate. Clin Perinatol. 2018;45(1):61-74.

- Harris DL, Weston PJ, Harding JE. Incidence of neonatal hypoglycemia in babies identified as at risk. J Pediatr. 2012;161(5):787-791.

- Adzick NS, De Leon DD, States LJ, et al. Surgical treatment of congenital hyperinsulinism: results from 500 pancreatectomies in neonates and children. J of Ped Surg. 2019;54(1):27-32.

- Lord K, Radcliffe J, Gallagher PR, Adzick NS, Stanley CA, De Leon DD. High risk of diabetes and neurobehavioral deficits in individuals with surgically treated hyperinsulinism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(11):4133-4139.

- Thornton PS, Stanley CA, De Leon DD, et al. Recommendations from the Pediatric Endocrine Society for Evaluation and Management of Persistent Hypoglycemia in Neonates, Infants, and Children. J Pediatr. 2015; 167(2):238-45.

Featured in this article

Specialties & Programs

Case:

A 1-month-old male infant presented to the pediatrician’s office because of poor feeding and increased sleepiness. His point-of-care glucose was 42 mg/dL. He was referred to the closest hospital for evaluation.The infant had been born at 38 weeks of gestation by scheduled C-section. He was large for gestational age with a birth weight of 4310 g. The pregnancy was uncomplicated except for the finding of glucosuria on the mother later in the pregnancy (earlier testing for gestational diabetes was negative). His initial glucose was 19 mg/dL, he was fed 35 mL of formula and his repeat glucose was 40 mg/dL. However, because of persistent hypoglycemia and hypothermia he was transferred from the regular nursery to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). In the NICU he required intravenous dextrose (D17.5%) for 3 weeks. Off the fluids and on fortified breast milk (24 kcal/oz), his glucoses were mostly >60 mg/dL with some occasional glucoses

Upon subsequent admission at 1 month of age, the infant was diagnosed with hyperinsulinism (HI). He was unresponsive to treatment with diazoxide, the only Food and Drug Administration-approved drug for HI, and was transferred to the hyperinsulinism program at CHOP for further evaluation and management. He was found to be heterozygous for a recessive, paternally inherited, disease-causing mutation in ABCC8, one of the two genes encoding the beta cell ATP-sensitive potassium channels (KATP channels). This finding was predictive of focal hyperinsulinism. Specialized imaging with 18F-DOPA PET scan revealed a focal lesion located in the head of the pancreas. (See Figure 3). He underwent a 20% pancreatectomy to remove the lesion with complete resolution of the HI.

Discussion: Hyperinsulinism is the most common cause of persistent hypoglycemia in neonates, infants, and children. HI is caused by dysregulated insulin secretion from the pancreatic ß-cells and can be the result of perinatal factors (also known as perinatal stress-induced HI), part of a syndrome (such as Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome), or monogenic, due to genetic mutations. While the monogenic forms of HI are rare (1 in 50000 live births), HI due to perinatal stress is quite common and can affect up to 50% of at-risk neonates. Clinical presentation of infants with HI is characterized by severe and persistent hypoketotic hypoglycemia. The most common and severe genetic form of HI affects the KATP channels, which are the targets of diazoxide, rendering this drug ineffective and thus, infants with this form of HI more frequently require pancreatectomy to control the hypoglycemia. There are 2 distinct histological forms of HI: a diffuse form, in which all pancreatic ß-cells are affected; and a focal form, in which only a small area of the pancreas is affected. Focal HI, which accounts for approximately 50% of these cases, can be cured by surgical excision of the lesion.

The management of infants with severe HI can be very challenging and requires a consorted cooperation between multiple disciplines. Recognizing this need, CHOP founded the Congenital Hyperinsulinism Center in 1998, creating the first multidisciplinary team (see Table 1) dedicated to the care of children with HI.

The clinical expertise of the center is unique. Since its creation, the program has evaluated and treated >1300 children with HI and has operated on >525 children with severe HI.

Patients from all over the United States—and from 18 countries—have come to Philadelphia for treatment. Our specially trained transport team accompanies patients, maintains their glucose levels in transit, and safely delivers them for additional treatment. Because our NICU and endocrinology unit see so many HI patients, nurses are especially attuned to caring for these babies before and after surgery.

We have the largest single center experience using 18F-DOPA PET for the pre-surgery identification and localization of focal lesions, with more than 400 patients undergoing the procedure. Our approach has significantly impacted outcomes, with 97% of infants—more than 215 patients—with focal HI now cured after surgery.

The center’s translational research program aims to address the knowledge gap (underlying genetic cause is unknown in 50% of cases) and lack of effective medical treatments (only 1 FDA-approved drug). Ongoing investigations range from molecular studies in cells to clinical trials with novel therapies in affected patients. The center’s designation as a CHOP Frontier Program in 2019 means additional funds for research and expansion that seeks to further innovate by using personalized medicine to treat children with the condition. Goals include building a multidimensional patient data collection platform, developing more accurate diagnostic tools for insulinomas, and accelerate late-stage clinical trials for a promising CHOP-patented compound that ameliorates HI.

Unfortunately, despite all the advances of the last 25 years, children with HI continue to have long-term consequences because of hypoglycemia-induced brain damage. Up to 48% of these children have neurodevelopmental deficits, including speech delays, learning disabilities, and fine and gross motor delays, among others. These problems are preventable if diagnosis is made early and treatment is effective.

One key goal of the 2015 Pediatric Endocrine Society guidelines for evaluating and managing hypoglycemia in neonates, infants, and children is the prompt recognition and evaluation of infants with persistent hypoglycemia disorders.

According to these guidelines, the severity and persistence of the hypoglycemia in the case discussed at the beginning of this article should have prompted a thorough evaluation to determine its underlying cause and the demonstration that the infant could maintain normal plasma glucose concentrations (which after the third day of life should be >70 mg/dL) prior to discharge. Just as a child with fever would not be sent home without an investigation for the underlying cause of the fever, a child with hypoglycemia should not be discharged without a diagnosis, because just as with fever, hypoglycemia is a sign, not a diagnosis.

References and Selected Readings

- Lord K, De Leon DD. Hyperinsulinism in the neonate. Clin Perinatol. 2018;45(1):61-74.

- Harris DL, Weston PJ, Harding JE. Incidence of neonatal hypoglycemia in babies identified as at risk. J Pediatr. 2012;161(5):787-791.

- Adzick NS, De Leon DD, States LJ, et al. Surgical treatment of congenital hyperinsulinism: results from 500 pancreatectomies in neonates and children. J of Ped Surg. 2019;54(1):27-32.

- Lord K, Radcliffe J, Gallagher PR, Adzick NS, Stanley CA, De Leon DD. High risk of diabetes and neurobehavioral deficits in individuals with surgically treated hyperinsulinism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(11):4133-4139.

- Thornton PS, Stanley CA, De Leon DD, et al. Recommendations from the Pediatric Endocrine Society for Evaluation and Management of Persistent Hypoglycemia in Neonates, Infants, and Children. J Pediatr. 2015; 167(2):238-45.

Contact us

Congenital Hyperinsulinism Center