What is pyloric stenosis?

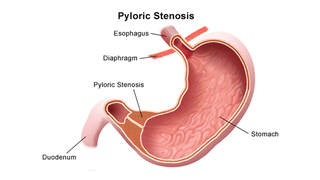

Pyloric stenosis is a thickening or swelling of the pylorus — the muscle between the stomach and the intestines — that causes severe and forceful vomiting in the first few months of life. It is also called infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis.

The enlargement of the pylorus causes a narrowing (stenosis) of the opening from the stomach to the intestines, which blocks stomach contents from moving into the intestine.

Pyloric stenosis usually affects babies between 2 and 8 weeks of age, but can occur anytime from birth to 6 months. It is one of the most common problems requiring surgery in newborns. It affects 2-3 infants out of 1,000.

Symptoms

Babies with pyloric stenosis usually have progressively worsening vomiting during their first weeks or months of life. The vomiting is often described as non bilious and projectile vomiting, because it is more forceful than the usual spit ups commonly seen at this age.

The severe vomiting can result in dehydration, which may cause your baby to sleep excessively, to cry without tears, or have fewer wet or dirty diapers during a 24-hour period. Some infants experience poor feeding and weight loss, but others demonstrate normal weight gain.

Constant hunger, belching, and colic are other possible signs of pyloric stenosis because your baby is not able to eat properly. Dehydration and electrolyte imbalance are common problems and can prolong a hospital stay.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing pyloric stenosis is made after taking a careful medical and family history and performing a physical examination. Radiographic studies are often recommended as well.

On exam, palpation of the abdomen may reveal a mass in the upper central region of the abdomen. This mass, which consists of the enlarged pylorus, is referred to as the “olive,” and is sometimes evident after your infant is given formula to drink.

Feeling the mass by palpation is a diagnostic skill requiring much patience and experience. There are often palpable (or even visible) peristaltic waves due to the stomach trying to force its contents past the narrowed pyloric outlet.

In addition to a complete history and physical exam, certain diagnostic procedures are used to confirm the diagnosis of pyloric stenosis:

- Ultrasound: the most common imaging test used to see the thickened pylorus.

- Upper GI series: a series of X-rays taken after your baby drinks a special contrast agent. The contrast agent illuminates the narrowed pyloric outlet and shows how the stomach empties.

Traditional X-rays of the abdomen are not useful in diagnosing pyloric stenosis, except when needed to rule out other potential problems.

Treatment

The first step in treating pyloric stenosis is to stabilize your baby by correcting the dehydration and electrolyte imbalance, which can have a serious impact on developing babies. Your child will receive an intravenous (IV) line to replace the fluids and salts she's lost through vomiting. This can usually be accomplished in about 24-48 hours. Blood tests will monitor how she's doing.

Once the blood tests come back normal, your baby's surgery — called a pyloromyotomy — will be scheduled. Surgery is necessary to treat pyloric stenosis.

Your baby will not be able to breast or bottle feed until the surgery has been performed to correct the pyloric stenosis. Many children are fussy in this pre-surgery time because they cannot eat, but it is extremely important to minimize the chances that they vomit. As a result, children with pyloric stenosis will remain on IV fluids to keep them hydrated before surgery.

Pyloric stenosis surgery

Surgery to correct pyloric stenosis is called a pyloromyotomy. In this procedure, surgeons divide the muscle of the pylorus to open up the gastric outlet.

At The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, the pyloromyotomy is done laparoscopically through small incisions and with tiny scopes. By doing laparoscopic surgery, we can minimize scarring, decrease potential infections and improve recovery time for children.

Your baby will receive general anesthesia to put her to sleep during the procedure. Once she's asleep, the surgeon will make small laparoscopic incisions in the belly. The surgeon cuts the muscle layer, then puts a numbing medicine into the area and closes the incision. These stitches will be under the skin and won't need to be removed.

Follow-up care after surgery

After your baby wakes up, she'll go to the recovery room for several hours, then to her own hospital room. Here's what to expect:

- Her incision will be covered with small strips of tape called Steri-strips®, or temporary glue called Dermabond®. The steri-strips will fall off on their own.

- The IV will stay in place until your baby is discharged; however, IV fluids will be stopped once your child is tolerating formula or breast milk.

- A few hours after the surgery, your child will be able to start feeding again. She may start off with Pedialyte® or go right to formula or breast milk. Either case will start with a small amount and increase slowly.

- Some vomiting may be expected during the first days after surgery as the gastrointestinal tract settles.

- If vomiting continues we may prescribe an antacid. The stomach lining can become inflamed with the persistent vomiting. The antacid will help to protect the stomach and can be discontinued at the post-operative visit.

- Your child's doctor or nurse will give her acetaminophen (Tylenol®, Tempra®, Panadol®) for pain.

Your baby will be discharged one or two days after surgery if she doesn't have a fever, is eating and not vomiting, and her incision isn't red or draining.

If your child is still having problems with frequent spitting up after surgery, she may be diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux (GER). You should follow up with your primary care physician to be evaluated for gastroesophageal reflux.

When to call the doctor

Be sure to call your child's doctor (at Children's Hospital, you should call 215-590-2730) if:

- You see any signs of infection at the incision site such as redness, swelling, discharge or bleeding

- Your baby's pain gets worse, and acetaminophen doesn't help

- Your baby develops a fever greater than 101 degrees F

- Your baby forcefully vomits large amounts, or her vomit is green

Long-term outlook

Pyloric stenosis is unlikely to reoccur. Babies who have undergone surgery for pyloric stenosis should have no long-term effects from it.

Why choose CHOP for your child's surgery

If your child needs surgery, you want to know their care is in the hands of the best, most compassionate team. CHOP's world-class pediatric surgeons and experienced staff are here for you.

Preparing for surgery

Find tips to prepare for your preoperative visit with CHOP’s pediatric general surgeons, and resources to help prepare your child for surgery.

Resources to help

Division of Pediatric General, Thoracic and Fetal Surgery Resources

We have created resources to help you find answers to your questions and feel confident with the care you are providing your child.

Reviewed by Pablo Laje, MD