What is tracheomalacia?

Tracheomalacia is the name for a wider or flatter windpipe (trachea) that collapses with breathing and coughing. Also described as a flexible or floppy windpipe, tracheomalacia may develop because of pressure from nearby blood vessels. It can also happen at the site of a tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) before the baby is born.

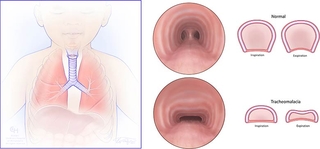

In tracheomalacia, the rigid part of the trachea is a different shape, and the flexible backwall is wider than usual. This allows the flexible wall to collapse into the airway. When this happens, it makes it difficult to breathe out forcefully, such as when crying or coughing, causing a barking sound. Tracheomalacia also makes it difficult for a child to clear out mucous and secretions from their lungs when coughing. This can lead to more severe respiratory illnesses like pneumonia.

Types of tracheomalacia

- Congenital tracheomalacia is also sometimes called type 1 tracheomalacia. The word “congenital” means a baby is born with the condition. While relatively rare, tracheomalacia is the most common congenital tracheal defect, with 1 in 2,100 children born with the condition. Babies born with tracheomalacia may have other congenital problems such as heart defects, developmental delay, esophageal abnormalities or gastroesophageal reflux.

- Acquired or type 2 tracheomalacia is the result of an injury, most often caused by repeated infections or having a tracheostomy tube for a long time. Acquired tracheomalacia is rarer than the congenital type.

- If the floppiness extends to where the trachea branches into the lungs, called the mainstem bronchi, the condition is called tracheobronchomalacia (TBM).

Symptoms of tracheomalacia

In congenital tracheomalacia, symptoms tend to appear when a baby is between 4 weeks and 8 weeks old as they start to breathe out forcefully enough to hear a barking sound. Sometimes, a child can show signs of tracheomalacia later in infancy or childhood during respiratory illness.

Symptoms of acquired tracheomalacia will appear after the injury or disruption of the airway occurs.

When babies and children try to cough and clear mucus from their airways, a typical airway will mainly stay open. However, an airway with tracheomalacia collapses and the mucous gets trapped in the lungs. This can lead to bronchitis or pneumonia. Symptoms can range from mild to severe and may include:

- Breathing noises that may change with position and improve during sleep

- Breathing problems that get worse with coughing, crying, feeding, or upper respiratory infections (such as colds)

- High-pitched sounds when breathing (called wheeze or stridor), more frequently heard during exhalation and more pronounced with exercise/exertion

- Rattling or noisy breaths

- Chronic chest congestion and frequent lung infections such as bronchitis or pneumonia (because the airway collapses, mucous gets trapped in the lungs)

- Apnea (halt in breathing) or cyanosis (bluish color to lips, skin) in infants

- Choking during feeding

- Chronic cough is often described as “barky” or “seal-like”

- Difficulty breathing during activity

Diagnosis of tracheomalacia

There is a lot of misunderstanding around tracheomalacia. That’s why it’s important to have your child seen by a team with the knowledge and experience to properly diagnose and treat this condition.

At Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, doctors from Pulmonology, Otolaryngology (Ear, Nose and Throat), and other subspecialty areas work together to diagnose and treat children with tracheomalacia. Tracheomalacia has similar symptoms to other lung and airway disorders. We will first listen to your child’s breathing sounds and take a medical history. Additional tests will then be necessary to confirm the diagnosis and determine the severity.

Your child may have some of these tests:

- Bronchoscopy: For this test, a tube with a tiny camera goes in the mouth and down the airway. This allows the physician to see the trachea while the child breathes and coughs.

- Laryngoscopy: This test is similar to a bronchoscopy, but it is used to evaluate the voice box and upper airway. It is often done at the same time as a bronchoscopy.

- Airway fluoroscopy: This is a type of X-ray that shows movement of the cartilage in the trachea.

- Esophagram: This is a type of X-ray that takes video images of the esophagus after the child drinks contrast or dye to see the shape it has when liquids are flowing through.

- Endoscopy: For this test, a thin, flexible tube with a light and camera on the end is inserted in the mouth. This allows us to see the esophagus, stomach and beginning of the small intestine.

- Computerized tomography (CT) scan: For this test, a lot of X-ray images are taken and combined to show an entire area of the body in detail.

- Pulmonary function tests: This lets us see how much air a child can breathe in and out.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): This is another type of test that lets us see an entire area of the body in detail.

Treatment of tracheomalacia

Treatment of tracheomalacia depends on the severity of a child’s condition.

In many cases, tracheomalacia can be mild enough to be managed medically with humidified air, nebulizers and medications to help make a cough more productive and overcome the floppiness. While tracheomalacia won’t go away completely, symptoms often improve as an infant grows and their tracheal cartilage gets stronger. Most children with tracheomalacia will improve by age 2 to the point that their symptoms are not severe enough to require surgery.

Respiratory infections can be dangerous for newborns with tracheomalacia. Coughing can cause the airway to collapse, making it even harder for them to breathe.

If a child also has gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), it is very important to keep this condition under control with medication.

Nonsurgical options we may use to improve respiratory symptoms include:

- Medication such as ipratropium bromide (Atrovent) or saline solution

- Chest physiotherapy: This is a way to clear the mucus in the lungs to decrease the chance of infection. Some children will be taught how to perform pulmonary hygiene, which are a series of exercises and procedures that help to clear their airways of mucus and other secretions.

- Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation: This involves wearing a mask over the nose and mouth so air can be gently pushed into the lungs. Examples include bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) or continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP).

In some severe cases, the child may need surgery to add stability and help keep their airway more open.

Surgery for tracheomalacia

In some cases, your doctor may determine that surgery is necessary. We offer advanced surgical options that can relieve your child’s symptoms and restore the function of their trachea. At CHOP, our general surgeons team up with pulmonary, ear, nose and throat, and gastroenterology specialists in the Esophageal and Airway Treatment Program to help decide which patients may benefit from surgery.

The type of surgery we do will depend on the severity of the condition and the location where the trachea is collapsing.

Factors determining the surgical approach include:

- Cartilage deformation

- Vascular anomalies

- Mediastinal masses

- Tracheoesophageal fistula

- Abnormal airway branching

- Chest wall and spine deformity

Surgical options for the treatment of tracheomalacia include:

- Tracheostomy to keep the airway open while the child hopefully outgrows the problem, performed by physicians in the Division of Otolaryngology (Ear, Nose and Throat)

- Pexy procedures (anterior aortopexy, anterior and/or posterior tracheopexy, anterior and/or posterior mainstem bronchopexy, posterior descending aortopexy and thymectomy) to attach the weak section of the trachea to other nearby organs or tissues to help hold it open

- Tracheal resection with end-to-end anastomosis

- Placement of external splints and internal stents, either absorbable or permanent, a rarer option

At Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, most upper airway surgeries are performed by otolaryngologists (surgeons who specialize in ear, nose and throat problems) in our Head and Neck Disorders Program or our Pediatric Airway Program. Surgeons collaborate with pulmonologists and other specialists as needed. Children with complex tracheomalacia, especially when related to esophageal atresia (EA) or tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF), also have the option of being cared for through CHOP’s Esophageal and Airway Treatment (EAT) Program, which specializes in diagnosing and treating children with complex esophageal and airway problems. These different programs collaborate often to ensure each child is cared for by the best team for them.

Outlook for children with tracheomalacia

Congenital tracheomalacia can range from mild to severe. For children with mild to moderate tracheomalacia, symptoms tend to improve with noninvasive therapies by the age of 18 to 24 months. As the cartilage gets stronger and the trachea grows, the noisy and difficult breathing may slowly improve. Children with severe tracheomalacia tend to struggle with airway clearance and frequent illnesses despite full medical treatments.

All children with tracheomalacia must be monitored closely by a pulmonologist or an ear, nose and throat doctor since the condition can lead to recurrent respiratory problems that can, eventually, injure the child’s lungs. Babies born with tracheomalacia may have other congenital abnormalities, such as heart defects, developmental delay or gastroesophageal reflux. For these children, appointments with additional specialists may be necessary.

Resources to help

Division of Pulmonary and Sleep Medicine Resources

These resources will help you find answers to your questions and learn more about your child's lung condition.