Jumpy, Hazy Eyes

Published on

Children's DoctorPublished on

Children's DoctorRead a case study from the Division of Ophthalmology about an infant presenting with abnormal eye movements and cloudiness who was evaluated for aniridia and possible WAGR syndrome associations.

A 12-week-old infant boy presented to his pediatrician after his parents saw abnormal eye movements and cloudiness. He was born at 33 weeks GA by cesarean section, triplet birth, at 4 lb, 8 oz. At 6 weeks his parents noticed he did not visually follow as well as his siblings, and at 10 weeks they noticed bilateral haziness of the corneas, as well as “jumping” eye movements which had become worse over the past 2 weeks. He also seemed more sensitive to bright lights than his siblings.

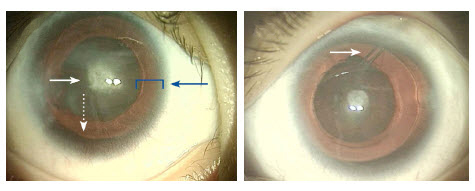

Figure 1: Infant with aniridia and glaucoma; note hazy corneas. The red reflex, cataract, and iris are obscured by corneal haze.

On examination, his head circumference is at the 50th percentile, weight 75th percentile for adjusted age, with normal appearing facial features and eyelids. The conjunctivae are white, but the corneas of both eyes appear to be hazy with “ground glass” appearance and normal in size. The pupils appear to be widely dilated or absent, and the pupillary red reflex appears dim with a central shadow (See Figure 1). There is pendular nystagmus symmetrically, but the patient is able to briefly follow his mother’s face.

Figure 1: Infant with aniridia and glaucoma; note hazy corneas. The red reflex, cataract, and iris are obscured by corneal haze.

On examination, his head circumference is at the 50th percentile, weight 75th percentile for adjusted age, with normal appearing facial features and eyelids. The conjunctivae are white, but the corneas of both eyes appear to be hazy with “ground glass” appearance and normal in size. The pupils appear to be widely dilated or absent, and the pupillary red reflex appears dim with a central shadow (See Figure 1). There is pendular nystagmus symmetrically, but the patient is able to briefly follow his mother’s face.

Observation of the triplet siblings demonstrates normal ocular appearance and visual fixation behavior in both. There is no family history of infantile or childhood eye or vision abnormality in the parents. There are no older siblings.

Discussion: The diagnosis of aniridia is made on careful clinical evaluation. The complete absence of iris, or small iris stump, gives the appearance of a widely dilated pupil. The condition is bilateral and symmetrical, present at birth, and may be associated with early onset of glaucoma with corneal edema and haze. Nystagmus is usually not present at birth, but develops within the first 2 months of life, with other frequently associated clinical ophthalmic features including anterior polar cataract (seen in this case as a shadow within the pupillary red reflex), progressive vascularization of the cornea (usually not present at birth but progressive during childhood), and frequent corneal surface abnormalities and recurrent spontaneous corneal erosion.

However, our diagnosis is not complete with the ophthalmic diagnosis of aniridia. Aniridia may occur in an autosomal dominant, heritable form and may also be associated with WAGR syndrome. (WAGR is an acronym for Wilms’ tumor, aniridia, genitourinary malformations, and growth retardation.) In infants with aniridia in whom there is a family history consistent with autosomal dominant transmission, the WAGR association can be excluded. Both WAGR and simple isolated aniridia can occur sporadically, but only isolated aniridia is seen in the familial, autosomal dominant pattern.

In our case, with no family history, we are obliged to evaluate for possible WAGR associations with chromosomal analysis (WAGR is associated with 11p13 deletion) as well as abdominal ultrasound for renal abnormalities and Wilms’ tumor. Up to half of sporadic cases of aniridia will have the WAGR deletion and develop Wilms’ tumor. Isolated aniridia is associated with mutations of the PAX6 gene, contiguous to the Wilms’ tumor gene on 11p.

The initial renal ultrasound was normal, but subsequent genetic testing demonstrated chromosomal deletion at 11p13, and repeat renal ultrasound at 1 year of age showed new bilateral renal masses. The patient was referred to the Cancer Center at CHOP. Surgical excision followed by systemic chemotherapy was curative.

The eyes were initially treated with topical aqueous suppressants (timolol and dorzolamide). Bilateral glaucoma surgery and bilateral cataract surgery were performed during the first 3 years of life (See Figure 2). Nystagmus and residual visual impairment persisted, and our patient also had global developmental delays requiring early intervention referral. His growth remains below the 25th percentile.

(L)Eye with aniridia, showing central cataract (white solid arrow), corneal haze, and peripheral “red reflex” (blue arrow). Only a small remnant of iris is visible (white dotted arrow). (R): Eye with aniridia, after placement of glaucoma tube shunt device (arrow). Notice the clearing of the corneal haze compared with Figure 1 and (L).

The permanent visual impairment expected with aniridia varies in individual cases, from moderate impairment (acuity of 20/100) to severe (acuity less than 20/200, legal blindness) and will require individualized adaptations for school and other activities. Most patients will also benefit from corrective glasses and usually use dark sunglasses outdoors due to the associated sensation of glare and light sensitivity. Surgical treatment for cataracts and for glaucoma is frequently required. Progressive ocular surface abnormalities may lead to corneal scarring and vision loss during the first and second decades, and other ocular treatments may also be needed.

In our case, the ocular diagnosis led to a significant syndromic diagnosis. Pre-symptomatic testing with ultrasound for renal abnormalities, and the early diagnosis and treatment of the bilateral Wilms’ tumor and anticipation of associated growth and developmental issues allowed our patient’s pediatrician and parents to comprehensively address his visual, medical, and developmental issues.

Fischbach B, Trout KL, Lewis J, Luis CA, Sika M. WAGR syndrome: a clinical review of 54 cases. Pediatrics. 2005;116(4):984-988.

Lee H, Khan R, O’Keefe M. Aniridia: current pathology and management. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86(7):708-715.

To refer a patient to CHOP’s Division of Ophthalmology, call 215-590-2791.

Contributed by: Monte D. Mills, MD

Categories: Ophthalmology, Children's Doctor Summer 2014