It’s not uncommon for patients who end up being diagnosed with Ewing sarcoma to first be treated for orthopaedic or sports injuries. The incidence of Ewing sarcoma in children, birth to age 20 years, is 2.9 cases per million, so it’s logical and cost effective to initially recommend OTC medications, rest and physical therapy for presumed sports-related pain.

The key element: “Treating physicians need to encourage patients and families to return if the pain doesn’t resolve within a few weeks,” says orthopaedic surgeon Kristy Weber, MD, Co-Director of the Bone and Soft Tissue Tumor Program, a collaboration of the divisions of Oncology and Orthopaedics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP).

That was the case for three patients — later treated at CHOP.

Hip pain in football player

S.C., a 14-year-old male football player, presented to the division of orthopaedics at his local hospital with right hip pain in January 2015. He was prescribed Motrin® and rest, which initially helped. He returned in February when the pain was worse. An X-ray did not show any obvious problems, so his doctor gave a preliminary diagnosis of bursitis and recommended physical therapy, with the caveat to come back if the pain didn’t resolve. He returned in May with worsening pain and inability to play sports. An MRI revealed a lesion in the right bony pelvis (ilium). He was referred to the Bone and Soft Tissue Tumor Program at CHOP.

New X-rays of the pelvis and an MRI were carefully reviewed and showed a destructive bone lesion in the right ilium extending into the surrounding muscles. Anne Marie Cahill, MD, Chief of CHOP’s Division of Interventional Radiology, and her team excel at minimally invasive needle biopsy and hand off the specimen to experienced musculoskeletal pathologists, who can make a diagnosis from a tiny sliver of tissue. A needle biopsy of S.C.’s right pelvic lesion revealed a Ewing sarcoma. Staging studies, including a CT scan of the chest and a PET-CT body scan revealed no other sites of cancer, which improved his chances for cure.

Given the tumor’s location, engulfing the entire right “wing” of the pelvis, treatment choices were chemotherapy and radiation (preserving the bone) or chemotherapy and surgery (removing the involved bone and all attached muscles with no option for reconstruction). Both scenarios included additional chemotherapy, under the direction of his oncologist Naomi Balamuth, MD, after the tumor was eliminated.

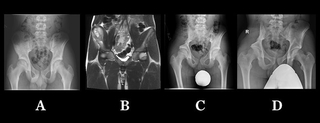

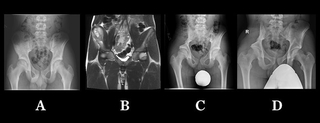

S.C. imaging, from left: (A) In initial X-ray, it’s difficult to see the lesion in the right ilium; (B) Initial MRIs show the soft tissue mass surrounding the right ilium; (C) Hip X-ray immediately after surgery shows what was removed with the cancer; (D) X-ray taken two years post-surgery shows hip bone has thickened.

Even though S.C. had aspirations to be a college football place kicker, his family chose the surgery route. To prepare for the surgery, Dr. Weber ordered specialized radiology images, (3D reconstructions of a pelvic CT scan) and an MRI, and reviewed these studies with the MSK radiology experts at CHOP in order to determine where to make the precise surgical cuts in the pelvic bone to balance complete removal of the Ewing sarcoma and maintenance of as much postoperative function as possible.

The final pathology results revealed 100 percent necrosis of the tumor and negative surgical margins.

Two years post-treatment, S.C. is cancer-free and is advancing toward his dream. He worked hard to rebuild his hip strength, and is the starting kicker for his high school team this fall.

Foot pain in soccer player

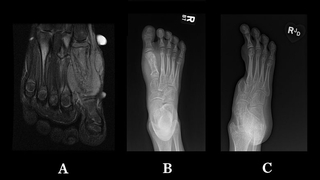

C.K., a 9-year-old boy, developed right inner foot pain while playing soccer. He visited a local orthopaedist, who initially recommended rest and ibuprofen, which helped. One to two months later, his pain continued and X-rays were taken, which showed no obvious lesions. He returned to playing sports and over the next three months experienced increased swelling and pain along the inner right foot. He returned for evaluation.

With a stress fracture suspected, he was told to stay off his foot and was given crutches and a hard shoe. He then had new foot X-rays and an MRI, which showed a lesion in his first toe with a surrounding soft tissue mass. He was referred to CHOP, where an ultrasound-guided needle biopsy revealed a Ewing sarcoma involving his right first metatarsal and first toe. A CT scan of the chest and a body PET-CT revealed only the localized Ewing sarcoma and no metastatic disease.

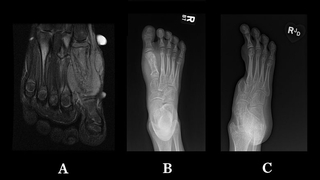

C.K. imaging, from left: (A) Initial MRI with a soft tissue mass surrounding the first metatarsal bone of the foot. Biopsy of the mass led to Ewing sarcoma diagnosis; (B) Pre-surgery X-ray shows the lesion in the first metatarsal; (C) Post-surgery X-ray showing removed first metatarsal and toe.

His care team, including Drs. Weber and Balamuth, recommended a treatment plan of chemotherapy, surgery to remove the toe and part of his midfoot, and additional chemotherapy. At the time of Ewing sarcoma removal, the tumor had 95 percent necrosis.

Unfortunately, there is not a functional prosthesis that can reconstruct the area of the foot that was removed, but that has not stopped C.K. from an active life. Two years after his diagnosis, he is free of cancer. He walks, skateboards, plays soccer and even surfs!

Preschooler with a limp

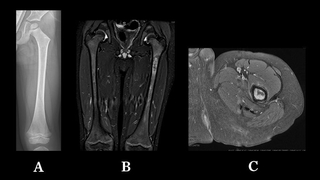

B.D, a 3-year-old boy, presented to his pediatrician with a limp in his left leg, which was initially attributed to a blister on his foot. When, months after the blister had healed, he was still having pain and a limp, his parents brought him to CHOP for an orthopaedic consult. X-rays were unremarkable, but since the symptoms were concerning, the doctor suspected an infection or tumor and ordered an MRI, which showed a well-defined area of marrow abnormality, without any bone destruction or soft-tissue mass.

The working diagnosis was osteomyelitis, and B.D., then 4, was set to undergo surgical debridement. Prior to an extensive approach to the femur, pediatric orthopaedic surgeon Wudbhav Sankar, MD, made a small incision and obtained an incisional biopsy with frozen section. Pathology diagnosed Ewing sarcoma. Alexandre Arkader, MD, a pediatric orthopaedic surgeon and orthopaedic oncologist who co-leads the Bone and Soft Tissue Tumor Program, came immediately to see B.D. and his family in-house and managed the child's care from that point on.

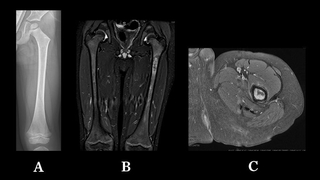

B.D. imaging, from left: (A) AP radiograph of the femur did not show any obvious bone lesion; (B) Coronal and (C) axial MRI images showed the abnormal signal in the intramedullary canal, without any extension into the soft tissues. This was a very non-specific appearance and suggestive mostly of an infectious process.

B.D. would need 14 cycles of chemotherapy, under the watchful supervision of pediatric oncologist Rochelle Bagatell, MD, with the surgery performed at the midway point. As this was a metaphyseal-diaphyseal lesion, and the hip joint was unaffected, the plan was to preserve the joint and also the proximal femur growth plate. Dr. Arkader recommended an intercalary resection of the femur with biologic reconstruction utilizing a vascularized fibula, also from B.D.’s left leg. For the microvascular repair of the bone graft, Dr. Arkader teamed with L. Scott Levin, MD, Chair of the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania.

The resection and reconstruction were successful, B.D. responded well to chemotherapy and, almost two years after diagnosis, he remains cancer-free. He is rehabbing well and is expected to resume normal growth and activities.

Bouncing back

“Kids are amazingly resilient,” says Dr. Weber. “The treatment of sarcoma is complex and frightening to patients and families, with the side effects of chemotherapy and radiation and the pain and potential functional limitations after surgery. But these kids still just want to get on with their lives. They understand they have cancer and they often understand the possible outcomes, including dying.

“But they put it aside and ask me, ‘What can I do this summer?’ They don’t want to sit in bed. They want to get out. If you don’t restrict them, once they’ve healed, they will rise to the occasion and do great things.”

Featured in this article

Specialties & Programs

It’s not uncommon for patients who end up being diagnosed with Ewing sarcoma to first be treated for orthopaedic or sports injuries. The incidence of Ewing sarcoma in children, birth to age 20 years, is 2.9 cases per million, so it’s logical and cost effective to initially recommend OTC medications, rest and physical therapy for presumed sports-related pain.

The key element: “Treating physicians need to encourage patients and families to return if the pain doesn’t resolve within a few weeks,” says orthopaedic surgeon Kristy Weber, MD, Co-Director of the Bone and Soft Tissue Tumor Program, a collaboration of the divisions of Oncology and Orthopaedics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP).

That was the case for three patients — later treated at CHOP.

Hip pain in football player

S.C., a 14-year-old male football player, presented to the division of orthopaedics at his local hospital with right hip pain in January 2015. He was prescribed Motrin® and rest, which initially helped. He returned in February when the pain was worse. An X-ray did not show any obvious problems, so his doctor gave a preliminary diagnosis of bursitis and recommended physical therapy, with the caveat to come back if the pain didn’t resolve. He returned in May with worsening pain and inability to play sports. An MRI revealed a lesion in the right bony pelvis (ilium). He was referred to the Bone and Soft Tissue Tumor Program at CHOP.

New X-rays of the pelvis and an MRI were carefully reviewed and showed a destructive bone lesion in the right ilium extending into the surrounding muscles. Anne Marie Cahill, MD, Chief of CHOP’s Division of Interventional Radiology, and her team excel at minimally invasive needle biopsy and hand off the specimen to experienced musculoskeletal pathologists, who can make a diagnosis from a tiny sliver of tissue. A needle biopsy of S.C.’s right pelvic lesion revealed a Ewing sarcoma. Staging studies, including a CT scan of the chest and a PET-CT body scan revealed no other sites of cancer, which improved his chances for cure.

Given the tumor’s location, engulfing the entire right “wing” of the pelvis, treatment choices were chemotherapy and radiation (preserving the bone) or chemotherapy and surgery (removing the involved bone and all attached muscles with no option for reconstruction). Both scenarios included additional chemotherapy, under the direction of his oncologist Naomi Balamuth, MD, after the tumor was eliminated.

S.C. imaging, from left: (A) In initial X-ray, it’s difficult to see the lesion in the right ilium; (B) Initial MRIs show the soft tissue mass surrounding the right ilium; (C) Hip X-ray immediately after surgery shows what was removed with the cancer; (D) X-ray taken two years post-surgery shows hip bone has thickened.

Even though S.C. had aspirations to be a college football place kicker, his family chose the surgery route. To prepare for the surgery, Dr. Weber ordered specialized radiology images, (3D reconstructions of a pelvic CT scan) and an MRI, and reviewed these studies with the MSK radiology experts at CHOP in order to determine where to make the precise surgical cuts in the pelvic bone to balance complete removal of the Ewing sarcoma and maintenance of as much postoperative function as possible.

The final pathology results revealed 100 percent necrosis of the tumor and negative surgical margins.

Two years post-treatment, S.C. is cancer-free and is advancing toward his dream. He worked hard to rebuild his hip strength, and is the starting kicker for his high school team this fall.

Foot pain in soccer player

C.K., a 9-year-old boy, developed right inner foot pain while playing soccer. He visited a local orthopaedist, who initially recommended rest and ibuprofen, which helped. One to two months later, his pain continued and X-rays were taken, which showed no obvious lesions. He returned to playing sports and over the next three months experienced increased swelling and pain along the inner right foot. He returned for evaluation.

With a stress fracture suspected, he was told to stay off his foot and was given crutches and a hard shoe. He then had new foot X-rays and an MRI, which showed a lesion in his first toe with a surrounding soft tissue mass. He was referred to CHOP, where an ultrasound-guided needle biopsy revealed a Ewing sarcoma involving his right first metatarsal and first toe. A CT scan of the chest and a body PET-CT revealed only the localized Ewing sarcoma and no metastatic disease.

C.K. imaging, from left: (A) Initial MRI with a soft tissue mass surrounding the first metatarsal bone of the foot. Biopsy of the mass led to Ewing sarcoma diagnosis; (B) Pre-surgery X-ray shows the lesion in the first metatarsal; (C) Post-surgery X-ray showing removed first metatarsal and toe.

His care team, including Drs. Weber and Balamuth, recommended a treatment plan of chemotherapy, surgery to remove the toe and part of his midfoot, and additional chemotherapy. At the time of Ewing sarcoma removal, the tumor had 95 percent necrosis.

Unfortunately, there is not a functional prosthesis that can reconstruct the area of the foot that was removed, but that has not stopped C.K. from an active life. Two years after his diagnosis, he is free of cancer. He walks, skateboards, plays soccer and even surfs!

Preschooler with a limp

B.D, a 3-year-old boy, presented to his pediatrician with a limp in his left leg, which was initially attributed to a blister on his foot. When, months after the blister had healed, he was still having pain and a limp, his parents brought him to CHOP for an orthopaedic consult. X-rays were unremarkable, but since the symptoms were concerning, the doctor suspected an infection or tumor and ordered an MRI, which showed a well-defined area of marrow abnormality, without any bone destruction or soft-tissue mass.

The working diagnosis was osteomyelitis, and B.D., then 4, was set to undergo surgical debridement. Prior to an extensive approach to the femur, pediatric orthopaedic surgeon Wudbhav Sankar, MD, made a small incision and obtained an incisional biopsy with frozen section. Pathology diagnosed Ewing sarcoma. Alexandre Arkader, MD, a pediatric orthopaedic surgeon and orthopaedic oncologist who co-leads the Bone and Soft Tissue Tumor Program, came immediately to see B.D. and his family in-house and managed the child's care from that point on.

B.D. imaging, from left: (A) AP radiograph of the femur did not show any obvious bone lesion; (B) Coronal and (C) axial MRI images showed the abnormal signal in the intramedullary canal, without any extension into the soft tissues. This was a very non-specific appearance and suggestive mostly of an infectious process.

B.D. would need 14 cycles of chemotherapy, under the watchful supervision of pediatric oncologist Rochelle Bagatell, MD, with the surgery performed at the midway point. As this was a metaphyseal-diaphyseal lesion, and the hip joint was unaffected, the plan was to preserve the joint and also the proximal femur growth plate. Dr. Arkader recommended an intercalary resection of the femur with biologic reconstruction utilizing a vascularized fibula, also from B.D.’s left leg. For the microvascular repair of the bone graft, Dr. Arkader teamed with L. Scott Levin, MD, Chair of the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania.

The resection and reconstruction were successful, B.D. responded well to chemotherapy and, almost two years after diagnosis, he remains cancer-free. He is rehabbing well and is expected to resume normal growth and activities.

Bouncing back

“Kids are amazingly resilient,” says Dr. Weber. “The treatment of sarcoma is complex and frightening to patients and families, with the side effects of chemotherapy and radiation and the pain and potential functional limitations after surgery. But these kids still just want to get on with their lives. They understand they have cancer and they often understand the possible outcomes, including dying.

“But they put it aside and ask me, ‘What can I do this summer?’ They don’t want to sit in bed. They want to get out. If you don’t restrict them, once they’ve healed, they will rise to the occasion and do great things.”

Contact us

Bone and Soft Tissue Tumor Program