What is myasthenia gravis?

Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune neuromuscular disease. In people who have myasthenia gravis, the nerves and muscles are unable to communicate properly. This is caused by abnormal antibodies that disrupt the connection between muscles and nerves. This disruption produces muscular weakness of varying degrees. The name of the disease comes from Greek words myo or “muscle,” asthenos or “without strength,” and gravis meaning “heavy.”

Myasthenia gravis is rare: about 10 in one million people are diagnosed each year, and just 10 percent of those diagnosed with the condition are children. The disease occurs in all age groups, ethnicities, and both genders.

When the condition is diagnosed in a child, the most common form is called juvenile myasthenia gravis (JMG). The juvenile form is more variable in its presentation and can mimic other illnesses, making the diagnosis challenging. For example, it is more difficult to detect auto-antibodies in the blood of children than adults.

Watch the video below to learn more about JMG.

Signs and symptoms of juvenile myasthenia gravis

The most common symptom of JMG is muscle weakness, which can range from mild to severe and impact a few or many muscles. Symptoms usually appear gradually, and worsen over time.

The most benign form of JMG, sometimes called ocular myasthenia, affects only the small muscles around the eye. The most visible sign is a drooping of the eyelid, or “ptosis” (pronounced “toh-sis”). Ptosis can occur on one or both sides (bilaterally). A careful evaluation of ptosis is critical, since it can be a symptom of multiple different illnesses.

In other patients, more muscles are affected and additional symptoms may include double vision, clumsiness, falling, difficulty speaking or swallowing, shortness of breath, and tiring easily while playing. Sometimes, children are mistakenly thought to be lazy, uncoordinated, or even unmotivated.

Causes of myasthenia gravis in children

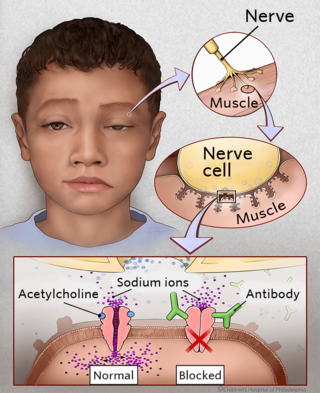

The reason children develop JMG is unknown. In people who have JMG, the nerves and muscles are unable to communicate properly. This communication process normally occurs with the help of a molecule (acetylcholine), which travels from nerves to muscle cells. In JMG, abnormal antibodies attach to the muscle, and prevent acetylcholine from working correctly. Eventually, the lack of nerve transmission leads to muscle weakness.

These abnormal antibodies are made by the immune system. The immune system, which normally functions to protect the body from foreign organisms, doesn’t work correctly in patients with JMG. While scientists do not yet fully understand why, it’s believed the thymus gland, an organ located in the chest, may be incorrectly influencing the immune system. Many patients with JMG demonstrate thymic dysplasia, or abnormal growth of the thymus. Clinical improvement can also be demonstrated when the thymus is removed in the majority of patients who undergo surgery.

Testing and diagnosis of myasthenia gravis

JMG is diagnosed by a comprehensive physical exam and several diagnostic studies. Each case is different, so the specific tests used can vary.

At CHOP, your child will have blood work completed to check for the irregular antibodies. If this test is positive, a JMG diagnosis will be confirmed. If the test is negative, other tests may be completed, including:

- Nerve stimulation testing: Communication between the nerves and muscles is tested by stimulating nerves repetitively.

- Electromyography (EMG): Single-fiber electromyography measures the response of a single muscle fiber to electrical impulses.

- IV Tensilon (edrophonium) testing: Edrophonium chloride, administered intravenously, can improve symptoms of myasthenia gravis for a brief period. This test is positive if significant symptom improvement occurs after administration. It must be done in a carefully monitored setting.

A CT scan or MRI may also be performed to take an image of the chest. These images will help with planning your child’s treatment, and help exclude the presence of a very rare tumor called a thymoma.

Treatment for myasthenia gravis in children

Non-surgical treatment

There are several medications that can be helpful in managing the symptoms of JMG. Two main types of medication are:

- Acetylcholine esterase inhibitors are the first line of treatment. They increase the availability of the molecule (acetylcholine) that helps nerves and muscles communicate. This medication is only marginally effective for severe symptoms. The most frequently prescribed medication is called pyridostigmine, also known as Mestinon. Side effects include diarrhea and muscle cramping.

- Immunosuppressive therapy (oral steroids and/or intravenous immunoglobulin) is used for both symptomatic relief and to stabilize patients pre-operatively. Doctors try to limit the time patients are exposed to these drugs in order to minimize side effects in children over time. For example, steroids can lead to decreased growth and obesity. At low doses, the steroids are better tolerated. If higher doses are required to manage symptoms, other immune-modulating medications may be considered.

To learn more about the non-surgical treatment options for myasthenia gravis, contact the following specialists:

- If your child’s symptoms are mainly in the eyes, contact the Division of Ophthalmology at 215-590-2791

- If your child’s symptoms primarily involve the rest of the body, contact the Division of Neurology at 215-590-1719

Surgical treatment

While medication can be highly effective in treating myasthenia gravis, we believe a combination of medical and surgical treatment offers the best chance of remission. Surgical treatment involves the removal of the thymus, a procedure known as a thymectomy.

The goal of surgery is to induce remission, improve symptoms, and reduce medication usage. However, its effect can sometimes take between months to years to occur following surgery.

For any questions regarding the surgical treatment of JMG, contact our Division of Pediatric General, Thoracic and Fetal Surgery at 215-590-2730.

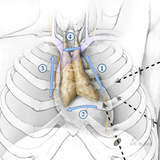

What is the thymus?

The thymus is an immune organ which lies beneath the breast bone in the chest. It is part of the body's immune system. We believe that removing the thymus reduces the amount of medical treatment required, and increases the probability for complete remission.

The thymus is very active early in life building immunity, but later in childhood the thymus becomes less relevant. Children generally do not experience any health problems as a result of no longer having a thymus.

What to expect during surgery

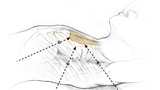

The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) has particular expertise in a minimally invasive (thoracoscopic) approach. The surgery is completed under general anesthesia and lasts about two hours.

During this procedure, three tiny incisions are made on the left chest. Each incision is around 7 mm (¼-½ inch) long. Modern surgical tools allow careful visualization and preservation of important structures in the chest, while also allowing a complete thymectomy. This is important because leaving some thymus behind may diminish the chances that the surgery will help.

All sutures are internal, and eventually dissolve on their own. The incisions are protected with surgical glue. Patients are usually ready for discharge the morning after the surgery.

Results of surgery

The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia has completed more of these procedures to remove the thymus in the pediatric population than any other hospital in the nation and we have a very low rate of complications. The average age of patients treated with thoracoscopic thymectomy is 7.6, ranging from 1 to 17 years of age.

Based on our current results, the minimally invasive approach to surgery is safe and effective. Patients have a shorter hospital stay, fewer complications, less pain, and a better aesthetic outcome.

Importantly, this operation does not instantly “cure” myasthenia gravis. Symptoms may begin to improve in weeks, months or years. In some cases, your child’s symptoms may even continue despite having had the surgery.

Immediately after the operation, patients will continue their medications exactly as they were taking them before surgery. Later, your child’s neurologist or neuro-ophthalmologist will carefully back off the medications if tolerated and symptoms do not recur.

Why choose us for juvenile myasthenia gravis

CHOP offers a unique, coordinated approach to treatment of juvenile myasthenia gravis. Multiple specialists will collaborate to determine the best plan of care for each child with JMG. Involved specialties can include Neurology, Ophthalmology, and Pediatric General Surgery.

Our focus is on producing the best possible outcomes for your child. This includes ongoing research to improve care for patients with JMG. In 2019, CHOP experts completed the largest cohort study of thymectomy in children with myasthenia gravis to date. The study reinforces the safety of thymectomy as a treatment option for juvenile myasthenia gravis, highlights the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration between medical and surgical providers involved in myasthenia care, and broadens the evidence of improved outcomes and reduced medications after surgery.

Our team is always available to answer any questions you may have.

Illustrations by: Eo Trueblood, MS

Why choose CHOP for your child's surgery

If your child needs surgery, you want to know their care is in the hands of the best, most compassionate team. CHOP's world-class pediatric surgeons and experienced staff are here for you.

Preparing for surgery

Find tips to prepare for your preoperative visit with CHOP’s pediatric general surgeons, and resources to help prepare your child for surgery.

Resources to help

Myasthenia Gravis Resources

Division of Pediatric General, Thoracic and Fetal Surgery Resources

We have created resources to help you find answers to your questions and feel confident with the care you are providing your child.

Reviewed by Pablo Laje, MD, John Brandsema, MD