Division of Nephrology

Learning your child has a chronic, life-changing condition like kidney disease is overwhelming. It can be challenging to cope with the condition's day-to-day impact on your child's health, and stressful to know it might affect their future well-being. We're here at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) for you.

In the Division of Nephrology, we work with your family to help your child with kidney disease. We provide services to support your child's physical, social and emotional health while living with this long-term, life-changing illness. We are here to answer your questions and offer assistance to make life with kidney disease more manageable.

How we serve you

Our Division of Nephrology provides world-class care for children with kidney diseases. Our physicians and staff are known for their ability to diagnose, treat and care for children with all forms of kidney disease. Here, you'll find superb clinical care and an equal measure of understanding and compassion.

-

Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring Program -

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) Clinic -

Dialysis Unit -

Glomerular Disease Clinic -

Hypertension Clinic -

Inherited Kidney Diseases (IKD) program -

Lupus Integrated Nephritis Clinic (LINC) -

Pediatric Kidney Stone Center -

Kidney Transplant and Dialysis Program -

Tuberous Sclerosis Clinic

Conditions we treat

We diagnose, treat and care for children with all forms of kidney disease, electrolyte disorders and hypertension.

-

Acute kidney injury (AKI) -

Blood in urine (hematuria) -

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) -

Congenital anomalies of the kidneys and urinary tract -

Hemolytic uremic syndrome in children -

High Blood Pressure (Hypertension) -

Kidney stones in children -

Lupus Nephritis -

Nephrotic syndrome in children -

Polycystic kidney disease -

Protein in urine (proteinuria) -

Urinary tract infection (UTI)

Why choose us for nephrology care

The Division of Nephrology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia is consistently ranked one of the top 5 programs in the nation by U.S. News & World Report.

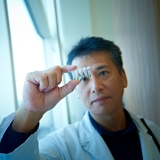

Meet your team

Here at the Division of Nephrology, we are known for our ability to diagnose, treat and care for children with all forms of kidney disease. We offer superb clinical care and a compassionate, family-centered approach.

Our locations

Access nephrology care in one of our many regional locations.

Our research

Our Division of Nephrology, with the establishment of the NIH Center of Excellence in Pediatric Nephrology, is focused on conducting innovative research contributing to breakthroughs in the care of kidney diseases in children.

Division of Nephrology resources

We have created resources to help you find answers to your questions and feel supported as you help your child cope with this condition.

Resources for professionals

We provide a variety of clinical and educational resources to support your care of pediatric patients with kidney-related conditions.

Kidney Stone Center and Diagnostic Innovation

The CHOP Kidney Stone Center Frontier Program focuses on developing new diagnostic tests to improve personalized management of early-onset kidney stone disease.

Clinical rotations and observerships

The Division of Nephrology offers customizable clinical rotations for clinical medical students and residents and observerships for undergraduate students.

Your donation changes lives

A gift of any size helps us make lifesaving breakthroughs for children everywhere.