Cardiac Center

Whether your child was born with heart disease (congenital) or developed a heart condition after birth (acquired), the top pediatric cardiologists and pediatric cardiothoracic surgeons at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) offer the answers and advanced care you and your child need.

Our team of more than 900 experts are specially trained to provide pediatric cardiac treatment and care for children from before birth through young adulthood. We are known around the world for our expertise in diagnosing and treating rare heart conditions with outcomes among the best in the world. We offer innovative technology, breakthrough research, state-of-the-art facilities and a full range of support services. Here, you and your child will have access to it all.

How we serve you

As one of the largest pediatric cardiac centers in North America, we offer a wide range of specialized programs and support services to meet your child's unique needs.

-

Acquired Autonomic Dysfunction Program -

Advanced Cardiac Therapies for Heart Failure Patients -

Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory -

Cardiac Center Nurse Navigators -

Cardiac Kids Developmental Follow-up Program -

Cardiac Nursing -

Cardiology Kawasaki Disease Program -

Cardiothoracic Anesthesiology -

Cardiothoracic Surgery -

Cardiovascular Connective Tissue Disorders Clinic -

Cardiovascular Exercise Physiology Laboratory -

Cardiovascular Institute (CVI) -

Cardiovascular Risk Assessment Clinic -

Center for Lymphatic Disorders -

Coronary Anomaly Management Program (CAMP) -

Cardiac Critical Care Medicine -

Electrophysiology and Heart Rhythm Program -

Familial Cardiomyopathy Program -

Fetal Heart Program -

Fetal Neuroprotection and Neuroplasticity Program -

FORWARD Program for Single Ventricle Care -

Heart Function, Transplant, and Ventricular Assist Device Program -

Heart/Lung Transplant Program -

Hypertension Clinic -

Infant Single Ventricle Monitoring Program -

Lipid Heart Clinic -

Pediatric Cardiology -

Pediatric Pacemakers & Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators (ICD) -

Philadelphia Adult Congenital Heart Center -

Preventive Cardiovascular Program -

Pulmonary Hypertension Program -

Pulmonary Vein Stenosis Program -

Recovery and Return Clinic -

Sports Cardiology Clinic -

Stutman Program -

Topolewski Pediatric Heart Valve Center -

TRACK Program -

Youth Heart Watch Program

Conditions we treat

-

Anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery (AAOCA) -

Anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA) -

Aortic regurgitation -

Aortic stenosis -

Ascites (chylous ascites) -

Atrial septal defect (ASD) -

Atrioventricular canal (AVC) defects -

Bacterial endocarditis -

Cardiac arrhythmia -

Cardiomyopathy -

Chest pain in children and teenagers -

Chylothorax -

Chylous pericardium (chylopericardium) -

Coarctation of the aorta -

Congenital heart disease (CHD) -

Congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (CCTGA) -

Cor triatriatum -

Double inlet left ventricle -

Double outlet right ventricle (DORV) -

Dyslipidemia -

Ebstein’s anomaly of the tricuspid valve -

Fainting (syncope) -

Heart block -

Heart failure in children -

Heart murmur -

Heart palpitations -

Heart transplant -

Heterotaxy syndrome (isomerism) -

Hypertension -

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) -

Interruption of the aortic arch -

Kawasaki disease -

Long QT syndrome (LQTS) -

Mitral valve defects -

Myocarditis -

Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) -

Pericarditis -

Plastic bronchitis -

Protein-losing enteropathy (PLE) -

Pulmonary atresia -

Pulmonary atresia with intact ventricular septum (PA IVS) -

Pulmonary hypertension -

Pulmonary regurgitation -

Pulmonary stenosis -

Pulmonary vein stenosis -

Rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease -

Single ventricle heart defects -

Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) -

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) -

Tetralogy of fallot (TOF) -

Total anomalous pulmonary venous return (TAPVR) -

Transposition of the great arteries (TGA) -

Tricuspid atresia -

Truncus arteriosus -

Vascular ring -

Ventricular septal defect (VSD)

Why choose us for cardiac care

We provide your child the highest level of care with outcomes among the best in the world. We are proud to be ranked one of the best pediatric cardiac programs in the nation by Newsweek.

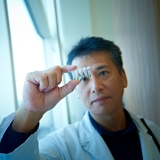

Meet your team

Your child will be cared for by one of the most accomplished teams of pediatric cardiology experts in the world. We make sure you and your child get the highest level of support.

Cardiac Center locations

Find top pediatric cardiologists and pediatric cardiothoracic surgeons who treat children and teens with heart disease.

Our research

The Cardiac Center is composed of more than 125 experts trained in a diverse range of specialties, with over 70 ongoing research projects and more than 220 active trials. Our mission is to improve the health and wellbeing of all children with heart disease.

Cardiac Center resources

We know that caring for a child with a heart condition can be stressful. To help you find answers to your questions – either before or after visiting the Cardiac Center – we’ve created this list of educational health resources.

Resources for professionals

Everything you need to support your patient’s health, created and updated by our CHOP community of experts.

Events

Cardiology 2026

Wednesday, Feb 25, 2026

Cardiac Center Welcome Guide

In this guide, you’ll meet your care team, find out what to expect during in- and outpatient procedures, and learn about all the resources to support your family along the way.

Preparing for your appointment

Learn what to expect during your child's outpatient visit at our Philadelphia Campus.

Patient outcomes: by the numbers

Our survival rates (surgical outcomes) are among the best in the world, placing us in the top tier of pediatric cardiac programs. We also perform more than 1,000 pediatric cardiothoracic surgeries each year.

Cardiac Grants Propel Cutting-Edge Research to Transform Outcomes for Children with Severe Heart Conditions

The collaborative efforts, led by researchers at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, aim to advance cardiac care treatment paradigm

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Team Performs Lifesaving Fetal Heart Surgery

For the fourth time in CHOP’s history, team successfully removed a rare tumor from baby’s heart while still in the womb.